1.6 Fragment 6

- Fragment 6, adapted from Hayles passage 5

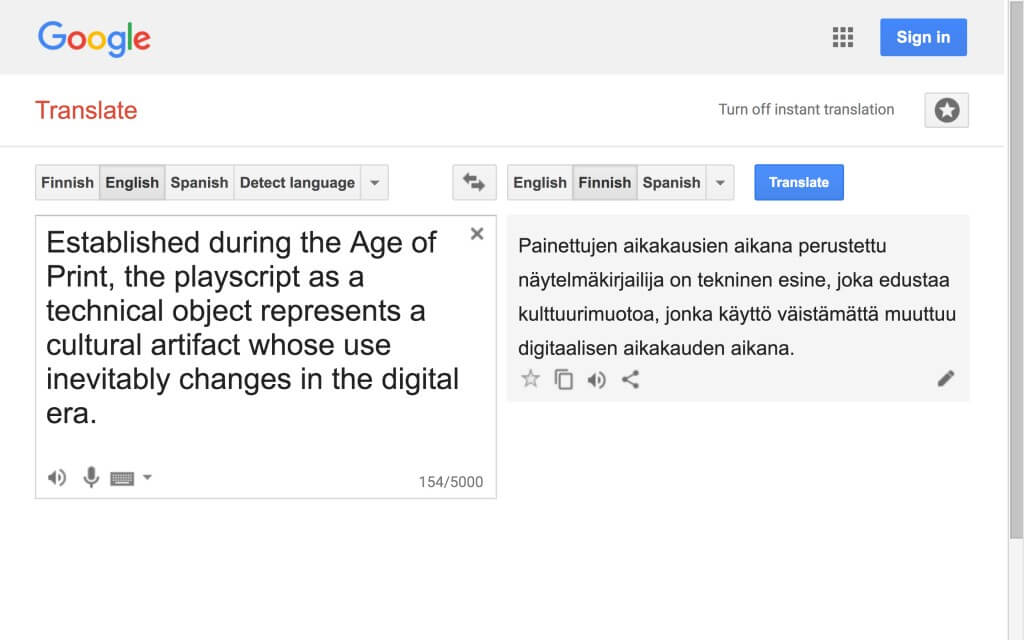

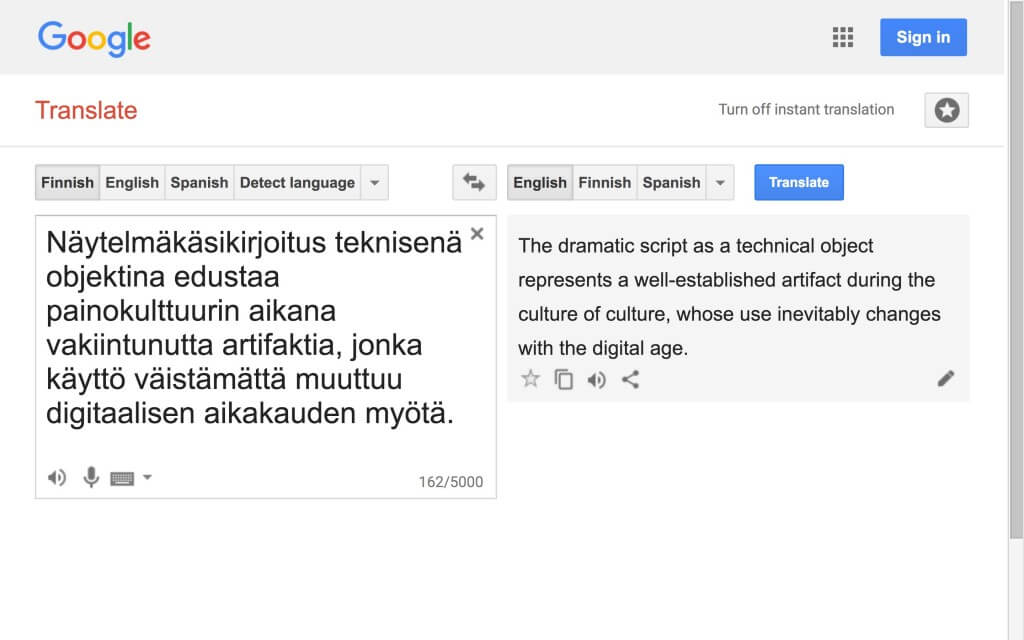

In fragment 6, DAR adapts the corresponding Hayles passage by proposing that the theater playscript be examined as a technical object that has established itself in the Age of Print and whose applications are changing in the digital era. The adaptation is somewhat surprising, as in her passage Hayles speaks of changes in mentality associated with the transition from print to digital culture rather than of any particular object (see adapted from Hayles passage 5). However, if we accept the argument that, for its part, the playscript reflects “mind-sets formed by print, nurtured by print, and enabled and constrained by print” (Hayles 2012, 1) than DAR’s choice seems justified.

In order to approach the question of the playscript as a technical object, I will briefly describe the various ways I have made use of it as a playwright and maker of dramatic theater. These uses can be roughly divided into three categories: 1) the script as literary product, 2) the script as tool for performance making, and 3) the script as (part of) performance. These categories do not represent a linear progression from, for example, dramatic to post-dramatic theater (1.6EN1), although my own trajectory has led through such phases to my current practice, which has come about as a result of—and alongside—this research. Rather, the various uses of the playscript contain echoes and reflections of each other, demonstrating the way in which technical objects in Hayles function as “repositories of change and, more profoundly, as agents and manifestations of complex temporalities” (Hayles 2012, 85).

In the early stages of my dramaturgy studies at Theater Academy Helsinki, in the late 1990s, my texts are criticized for being “too literary,” unsuitable for performance, the mouths of the actors (1.6EN1.5). This no doubt relates to the fact that, before writing plays, I have written lyrical poems and short stories. My relationship with language has, in other words, been conditioned by reading and writing poetry—and only to a lesser degree by seeing and reading plays. Thus, I could be seen to have conceived of the playscript as a book or comparable literary product—differing from a publication of poetry or short stories only in literary genre—in relation to which the stage performance is secondary (the presentation of a printed play).

Video 1.6.1 EN

In my interpretation of fragment 6, the development cursorily described above reflects the way—in the “object-centered view” dealt with by Hayles—technical objects do not appear as unchanged entities that remain the same regardless of time and place. Instead, they are “temporary coalescences” arising in charged fields whose “complex temporalities enfold past into present, present into future.” (Hayles 2012, 86) In the charged field of performance-making, playscripts are technical individuals that comprise technical elements (individual parts of the script such as scenes, acts, and parentheses) and that form a part of the technical ensemble which is the performance itself (1.6EN2). When the ensemble changes—for instance, as artistic goals change—the technical elements and along with them the technical individuals also change. Past uses and their established structures—e.g. how the text contained by the script is structured for reading and performing—remain as, at least, traces in the technical individuals, which is how they begin to form temporal layers. (Hayles 2012, 87)

Essential in this evolutionary view of technical objects is the fact that they “are always on the move toward new configurations, new milieu, and new kinds of technical ensembles.” Playscripts do not only contain complex temporalities but they also carry such temporalities with them in “a constant dance of temporary stabilizations.” Technical ensembles create technical individuals to meet their needs—somewhat like performances create tools for their often idiosyncratic purposes—, but technical individuals also lead to the creation of technical ensembles. The example Hayles makes reference to is the automobile, which creates the need for a network of paved roads (1.6EN3). Thus the technical individual anticipates the future in the present (future road network in the current car), while it also carries with it traces of the technical ensemble that has produced it. (Hayles 2012, 89) Owing to this potentiality, the playscript could then be thought of as a powerful tool for the production of all kinds of performances, especially those not yet present in the current technical milieu. By extension, the question concerning the playscript could be formulated in terms of what kind of (future, yet unknown) performance does the script currently imagine.

Also relevant for the purposes of this research—and perhaps more generally for performance—is the concept of “concretization,” borrowed by Hayles from Gilbert Simondon. The term relates to technological change and more specifically to the ability of technical elements to “travel” from one technical individual to another. By concretization Simondon refers to inventions that “resolve conflicting requirements within the milieu in which a technical individual operates.” The technical element—stage directions, for example, in the case of the playscript—must be sufficiently flexible to be able to assume its place in the new technical individual, and on the other hand firm enough to maintain that place. This fulfillment of conflicting demands requires negotiation, which in the case of performance means dramaturgical work (adaptation). Before the “traveled” element becomes a fully functional part of the technical individual, it must change from “abstract” (not yet internalized) to “concrete” (an organic part). Concretization, therefore, implies the integration of “conflicting requirements into multipurpose solutions that enfold them together.” (Hayles 2012, 88) In the context of this project, concretization applies in particular to the way the artistic parts of the research adopt and adapt elements of a playscript that I have written well before I might have even imagined the ensembles to which its parts are later attached.

Notes

1.6EN1

By postdramatic I refer here to Hans-Thies Lehmann’s analysis in Postdramatic Theatre, in which the following features of performance are characteristic of the postdramatic: absence of illusion, addressing audience directly, detachment from closed (Aristotelian) drama towards open communication, real-timeness, stage as site of performance, absence of characters (as there is no symbolic world to represent), corporeality, heightened physical presence, shared time (as opposed to killing or denying time), detachment from aesthetic sphere (i.e. an artistic ideal that cherishes integrity of form and excludes the outer world), detachment from traditional forms of drama (which are already part of our perception mechanisms). (Lehmann 2006EN)

1.6EN1.5

Dramaturgy studies at the Theater Academy Helsinki have traditionally included playwriting, although all students are not required to write plays. Thus the approach differs significantly from most North American theater institutions, in which dramaturgy and playwriting are pursued in separate programs.

1.6EN2

Here I follow the division into technical individuals, elements, and ensembles that Hayles takes from Gilbert Simondon’s Du mode d’existence des objets techniques (2001). In Hayles’s reading, technics for Simondon is “the study of how technical objects emerge, solidify, disassemble, and evolve” (Hayles 2012, 87).

1.6EN3

What leads to the car, in turn, is the concentration of production into plants and the legal provisions under which these plants must be situated away from inhabited areas (Hayles 2012, 89).