3.6 Fragment 26

- Fragment 26

What live writing (LW) and writing through contemporary self-translation (WTCST), as described in fragment 26, have in common is the use of Google Translate as both medium and writing platform. In other respects, the differences between the writing methods are more notable than their similarities. In this response, I will allude to some aspects of an ongoing discussion in translation studies on more traditional forms of self-translation (3.6EN1). The purpose of this brief digression is to approach the practice of WTCST from another perspective and to continue exploring how it, along with LW, could comprise a constructive technogenetic intervention, such as those discussed by Hayles (see 3.5).

In WTCST, algorithmic translations are working material that is altered and rewritten. Their most usable parts are included as such or with minor modifications in the text-in-progress. At the very least, algorithmic translations are used as points of reference in the writing processes, when the writer compares their own text to them. In comparison to LW, in WTCST the writer has far more power over their text, as they do not need to negotiate writing it with several other concurrent (human) performers. In principle, they can treat algorithmic translations as they wish, without accountability of any kind (3.6EN2).

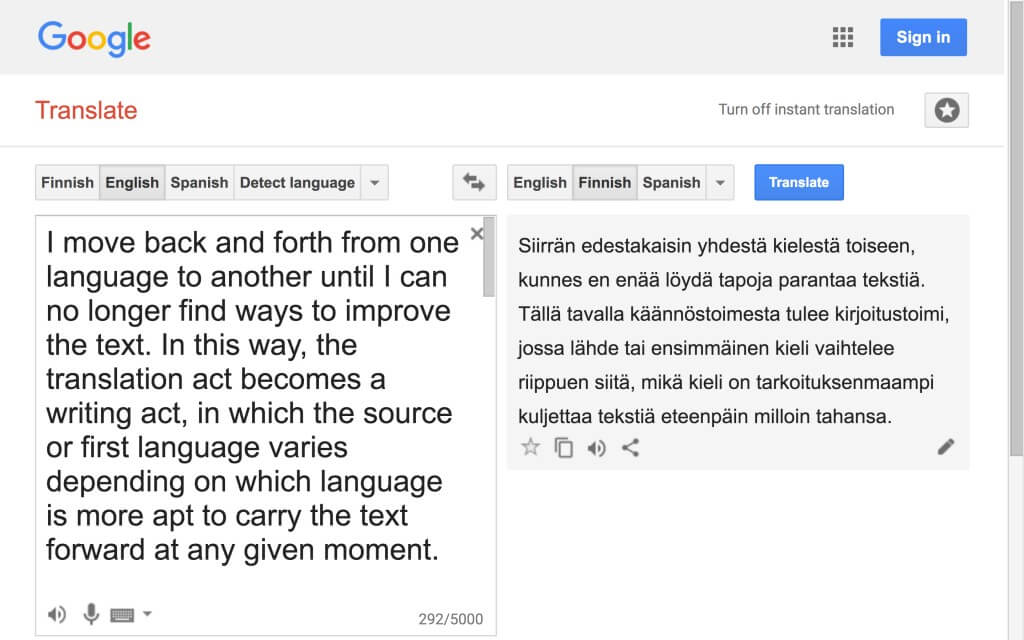

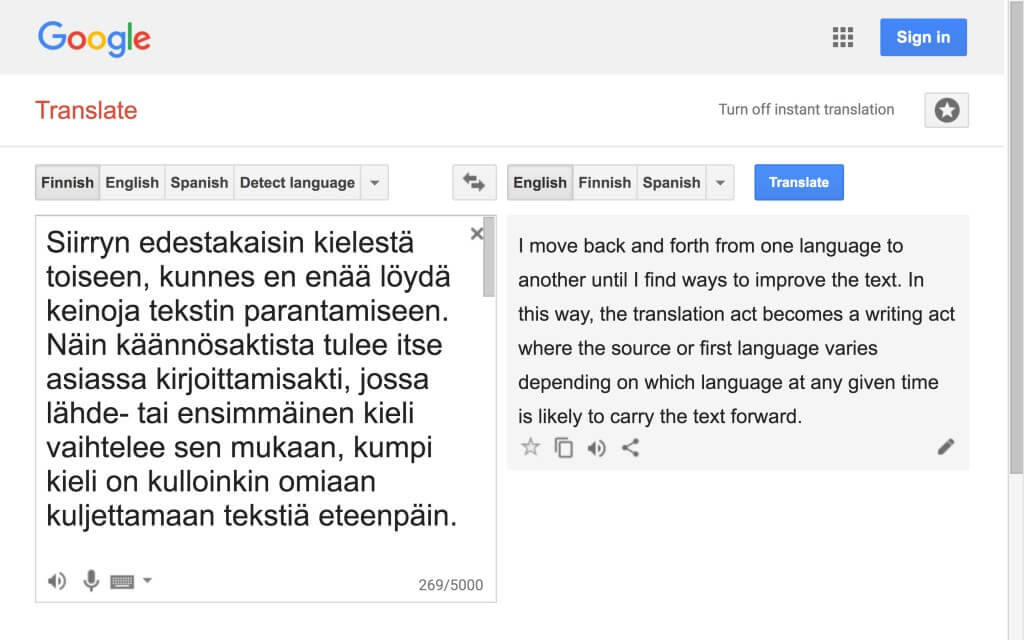

My own take on WTCST mirrors closely that of DAR’s. More specifically, I am writing my commentary on DAR’s adaptation by typing text into Google Translate and using its automatic translations as the basis for the parallel versions of my text. First, I write in either English or Finnish—depending on which language seems more active or “apt,” as DAR writes (see fragment 26)—and then stop to consider the program’s translation. Depending on how useful it appears, I may turn to rewrite the translation or continue to write the first-language version.

When I have completed the parallel (or second-language) version, I go back to the previous version and edit it by making corresponding changes to it. More often than not, this will lead to making more changes, which, in turn, leads to returning to the parallel version (of course, by this time, they are both simply each other’s parallel versions). This reciprocal movement between different versions and languages continues until I feel I can no longer improve on either version—or, as André Brink describes it, “at a certain stage, I just have to say ‘that’s enough’” (Peñalver 2015, 149). As the translation prompts me to go back and edit the original, which, in turn, compels me to change the translation, it is clear that the terms “original” and “translation” are impractical and inexact in this context. Rather than a process of translation, what is at stake is a process of writing through translation.

As mentioned in 3.1, self-translation of this kind is a means for thinking, a method of carrying out—or, at the very least, intensifying—research. The act of translating into another language sets up a self-reflexive space, akin to a rehearsal room with mirrors, in which the parallel texts reflect back on each other. This enables a cross-linguistic examination of one’s thoughts that would, if one were to write in just one language, be missing or only externally imposed (by an editor, for instance).

Self-Translation as Extension, as New Stage

Translation studies scholar Rainier Grutman refers to poet and translator Jacqueline Risset, whose essay “Joyce Translates Joyce” (1984) deals with James Joyce’s “Italianizations” of his own unfinished text fragments. In Risset’s view, conventional translations (of Joyce) tend to be “hypothetical equivalents of the original text” compromised by their “fidelity and uninventiveness.” Joyce’s own versions of the texts, in contrast, constitute “a kind of extension, a new stage, a more daring variation on the text in progress.” (Risset according to Grutman 2011, 258–259, emphasis added)

Risset’s idea of self-translation as an “extension, a new stage” aptly describes how self-translation works here: knowledge is produced through the translation act itself. Self-translation is both method and research subject, an ambiguous activity that both enables and is the focus of the research. In the case of WTCST and this project, the research would not exist in its present form without self-translation.

Grutman points out that the main difference between self-translations and translations made by others lies in how they are produced. Quoting Brian Fitch, Grutman writes, “a double writing process more than a two-stage reading-writing activity, [self-translations] seem to give less precedence to the original, whose authority is no longer a matter of ‘status and standing’ but becomes ‘temporal in character’.” As the temporal separation between original and translation narrows and virtually disappears, “the distinction between original and (self)translation [–] collapses, giving way to a more flexible terminology in which both texts can be referred to as ‘variants’ or ‘versions’ of comparable status.” (Grutman 2011, 259, emphasis added)

As this suggests, the adjacent texts of this research are “variants and versions of comparable status,” in spite of the asymmetric global status of the natural languages they are written in (see 4.1). (This is highlighted by the fact that the languages are, in different parts of this thesis, alternately in right- and left-hand columns, as if “source” and “target” languages were changing place.) Expanding on the temporal relationship of original and translation, Grutman makes a useful distinction between “simultaneous self-translations” and “consecutive self-translations,” the former being “produced even while the first version is still in progress,” and the latter “prepared only after completion or even publication of the original.” (Grutman 2011, 259)

Self-Translation as Artistic Research, Artistic Research as Self-Translation

Simultaneous self-translation is, according to Grutman, “a type of cross-linguistic creation, where the act of translation allows the bilingual writer to revisit and improve on earlier drafts in the other language, thereby creating a dynamic link between both versions that effectively bridges the linguistic divide” (Grutman 2011, 259). Expanding on this point, I claim that self-translation effectively bridges not only linguistic divides, but also divides between artistic and discursive practices. When they take on the task of translating between artworks and discourses, going back and forth in a somewhat similar manner as described above, artistic researchers are nothing if not self-translators.

In this hypothesis, artistic research emerges only after it has been extended by self-translation, only after a new stage has been set up for it, only after it has been (at least) twice written. Without this extension, this new stage, we would remain at the starting points of the research (in this case, at the stages upon which the artistic parts of the research are performed). It is here where the possibility of self-translation as artistic research, and artistic research as self-translation, appears (3.6EN3). It could even be said that the relationship of the artwork to the written work is reminiscent of the interdependent relationship of the parallel texts in self-translation, which Grutman—when writing of Samuel Beckett’s work—describes in terms of a calling: “each monolingual part calling for its counterpart in the other language” (Grutman 2011, 259, emphasis added). In a similar fashion, the artistic and written parts in artistic research call upon each other, discontent if not quite insufficient without the other.

Notes

3.6EN1

From the point of view of research that utilizes different forms of automation, it is interesting to note that in English self-tranlation is also known as autotranslation (Bassnett 2013, 285). The basic definition of self-translation is translation of the author by the author.

3.6EN2

DAR is an unusual case in that Google’s “original” translations are still visible in the translation boxes.

3.6EN3

Having systematically translated and retranslated his philosophical texts in up to four languages, Vilém Flusser stands out as a remarkable example of integrating translation into creative thought processes. According to Rainer Guldin, Flusser “used the technique of self-translation to distance himself from his texts in order to verify their inner coherence and formal qualities” (Guldin 2013, 95, emphasis added).