3.7 Fragment 27

- Fragment 27

Fragment 27 supplements our understanding of the technogenic interventions discussed in 3.5 and 3.6 by highlighting the algorithms themselves. It is appropriate to ask, whether code in fact constitutes the third language in the “binary language system of the self-translator,” as DAR calls it. WTCST would then be a multilingual system of two natural languages and one or more programming languages, in contrast to the more traditional bilingual systems of self-translation dealt with in translation studies (see Grutman 2011 and 3.6).

DAR’s contribution is important because it implies what WTCST actually intervenes in. By giving the third, machinic language the position it deserves in the whole, my claim can be supplemented with the following: WTCST intervenes in human reading and writing practices by introducing a working model of how natural and programming languages can be productively combined in the production of text and knowledge. The intervention is by nature technogenic, as it involves the gradual development of humans and technologies over a fairly long period of time. It can also be constructive as it presents a way in which digital media can, through their algorithmic propositions, play a productive part in reading and writing.

This is also related to the question raised in 3.5, concerning the relationship of the research with code. How has our understanding of—or relationship with—code changed over the course of the research? With a few minor exceptions, we have not learned to code. Instead, by constantly exposing ourselves to its linguistic impact, we have become closer with code in other respects. One cannot learn how translation algorithms work by translating texts back and forth with machine translation, even if the process is continued endlessly. Through looping, however, one can learn to recognize some features or tendencies of how different algorithmic systems treat natural languages. These features, in turn, point to wider developmental trends in the ways algorithmic processes may be modifying languages on a global level.

The clearest indication of our changed understanding of the nature of code is the recognition of programming as a form of writing that deserves a comparable status to other forms of writing in art and research fields. Art and research can be carried out by writing playscripts and librettos and so too by writing algorithms, which is why algorithmic writing is likely to continue to garner more attention in the performing arts and in artistic research (3.7EN1). Algoristic practices (3.7EN2), i.e. artistic practices that bring together artistic and computing expertise, are of particular interest in this regard, as are the convergences of programming and dramaturgy mentioned in 2.6.

Language of the Algorithms

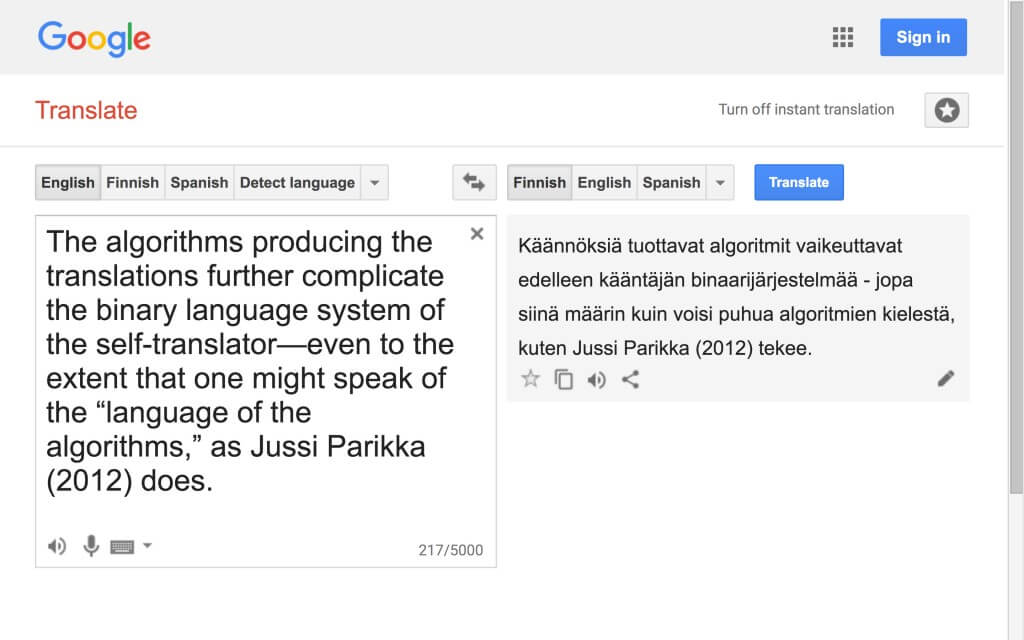

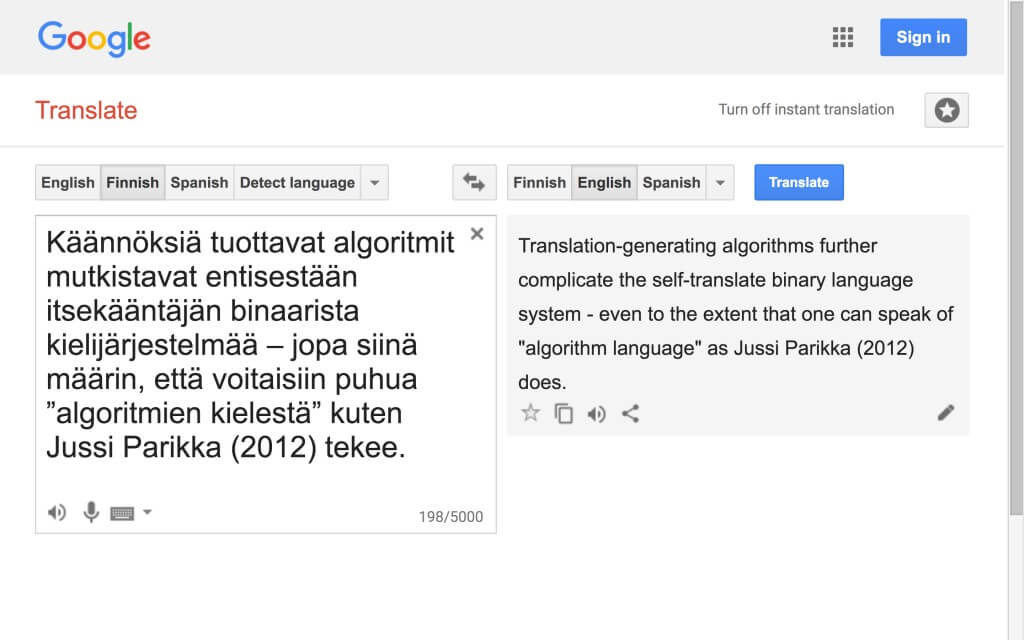

As important as DAR’s contribution in this context is, what compromises the academic credibility of fragment 27 is a puzzling flaw. The words quoted in the fragment and accredited to media theorist Jussi Parikka do not appear in the referenced text. In “Statistical Machine Art,” Parikka writes of an “algorithmic take on language” and an “algorithmic level of language” and so too of Google Translate as a “mediatic link between [-] various human languages” (Parikka 2012, 4–5). However, the expression “the language of algorithms” does not appear in the text.

Since we do not have the means to trace the cause of the miscitation, we are left with two likely explanations. Either the mistake is purely human or human-algorithmic. In other words, either DAR has unintentionally misquoted Parikka—perhaps having forgotten to check the citation later—or then the error is the result of an overlooked algorithmic edit that has, through the multiphase self-translation process, found its way into the text. In any case, the mistake is fortuitous because it draws attention to the ambiguity of the expression “language of the algorithms,” which can refer literally to code or to natural language in its algorithmically produced or altered form.

In this connection, we are confronted with the question whether algorithms have their own recognizable way of writing or treating language, a “voice” of their own (3.7EN3). Referring to this possibility, Frederik Kaplan has argued that in these times of automated text completion and other textual algorithmic interventions, we need to be particularly vigilant and language-aware as the built-in mechanisms work constantly on the language we type (or speak) into digital systems. Identification of the potential algorithmic dialects and mixed languages is, at least for the time being, our responsibility, because algorithms themselves are, paradoxically, inept at identifying them (3.7EN4). (Kaplan 2014, 61–62) “Google’s aesthetico-political digital economy” (Parikka 2012, 7) is an example of the conflicted fields of interest between individuals and corporations that Hayles refers to (Hayles 2012, 18), which in this case influence future manifestations of natural languages. This, of course, is a point of considerable interest and concern for self-translators utilizing Google’s and other corporations’ programs as central facets of their working methods.

Notes

3.7EN1

Annie Dorsen’s algorithmic theater is an example of an ambitious attempt to incorporate algorithms into all facets of the creative process, including writing (Dorsen 2012).

3.7EN2

Visual artist Roman Verostko defines algorists as “artists who create art using algorithmic procedures that include their own algorithms” (Verostko n.d., 1).

3.7EN3

In connection with his exhibition Lingua Franca, Australian contemporary artist Baden Pailthorpe speaks of “the ‘voices’ of Google’s algorithms becom[ing] more and more present in the translations” of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (Pailthorpe 2012). Pailthorpe’s exhibition is the subject of Parikka’s essay.

3.7EN4

In part, this is what gives rise to the “linguistic wars” Kaplan mentions, in which internet search engine algorithms battle with algorithms trying to artificially manipulate their search results (Kaplan 2014, 58).