3.5 Fragment 25

- Fragment 25

In this response to fragment 25, I will deal with technogenesis (the co-evolution of humans and technologies) by presenting an adaptation video and a series of questions. The purpose of the video and the questions is to clarify how this research approaches the hypothesis presented by Hayles. As a concept, technogenesis refers to a remarkably broad and complex phenomenon, which is why it must be approached attentively. How We Think is also a comprehensive and challenging work, the interpretation of which requires patience and careful reading. For these reasons, I have decided to imitate DAR here and create a Hayles adaptation of my own, albeit in the form of a video text.

In , I have assembled, translated, and adapted nearly all the passages of How We Think in which Hayles explicitly addresses technogenesis. The impetus for this is the deepening relationship of the human writer and digital media, evident in fragment 25 and throughout this research. I turn to Hayles in order to acquire more specific conceptual tools for describing this development within the framework of my research. For this purpose, I employ the most effective means I am familiar with, translation and adaptation. In this context, this strategy appears as a methodological tool, as a means of acquiring, modifying, and re-interpreting knowledge—in short, as a means of thinking.

is literally a paraphrase, in that the ideas presented in it are not my own. Instead of simply referring to Hayles, I have, however, found it necessary to present a rewording of parts of her text (which, in many cases, fails to capture the elegance of the original). The rationale for such a precarious textual exercise is this: in order to work in earnest with the complex concepts Hayles presents, in order to really access the lines of thought put forward, I need to tamper with the material text itself and not only the concepts. Ultimately, this churning or churning up of the textual surface aims at creating distance from the ideas presented by the author and space for individual reflection to enter. In the latter part of this response, I list a series of questions that, in light of , seeks to comprehensively present the relevance of technogenesis for this research.Hayles on Technogenesis

Video 3.5.1 EN Source referenced in video 3.5.1: Hayles 2012

19 Questions on Technogenesis

- How have we, the writers of this research, developed with machine translation and speech recognition?

- How have we adapted to these technologies? Can we say that the technologies have adapted to us? If so how?

- As writers, have we become more adaptive, more flexible, as a result of our interconnectedness with digital media?

- Has our relationship with or understanding of computer code changed over the course of the research process?

- Have we adopted models from the technologies for use elsewhere?

- Have we changed neurologically/physically/cognitively due to our extended experimentation with digital media?

- Has our understanding of the machines we use as objects changed?

- In the writing methods themselves, how are our responses intertwined with machine processes?

- Can the writing methods be understood as constructive technogenetic interventions? What specifically do the they intervene in?

- What means do we have to evaluate the technogenetic changes occurring in this research?

- Do we have an understanding of how machine cognition factors into the writing processes?

- Ultimately, have we changed as writers? If so, how?

- Do our writing methods or the technical systems enabling them constitute complex adaptive systems?

- What is our relationship with multinational corporations such as Google?

- Where will our adaptation, both linguistic and biological, ultimately lead?

- Is our approach broad, flexible and subtle enough to describe the potential technogenetic changes happening within the research?

- What understanding of writing and reading is suggested by the research at a more general level?

- In the future, how are we to find new means of intervention?

- Do our writing methods develop our human flexibility and plasticity rather than our ability to resist the influence of digital media and their manufacturers?

How Has Machine Translation Changed

To begin unpacking the questions listed above, I will conclude this section by alluding to a few techno-linguistic aspects of this research that are relevant for the consideration of technogenesis. The central digital medium of the research, algorithmic translation, is in a state of constant change. Machine translation may not have lived up to the expectations of Warren Weaver’s “Tower of Anti-Babel” (3.5EN1), but it continues to evolve as new, more efficient and accurate approaches replace older ones.

In fact, at the moment, in 2017, “we are in the midst of a revolution of sorts in machine translation, with the ground moving fast beneath our feet,” as Rita Raley writes (Raley 2018). Generally, a transition is happening from the statistical methods still recently thought to be most effective to neural machine translation, which utilizes new forms of machine learning, especially artificial neural networks modeled on their biological counterparts (3.5EN2). In mathematical linguistics, there is still some debate on just how decisive a revolution neural machine translation ultimately is, but even those raising critical questions describe it as “a new paradigm in the MT field” or, at the very least, “a step forward” (Castilho et al. 2017, 109).

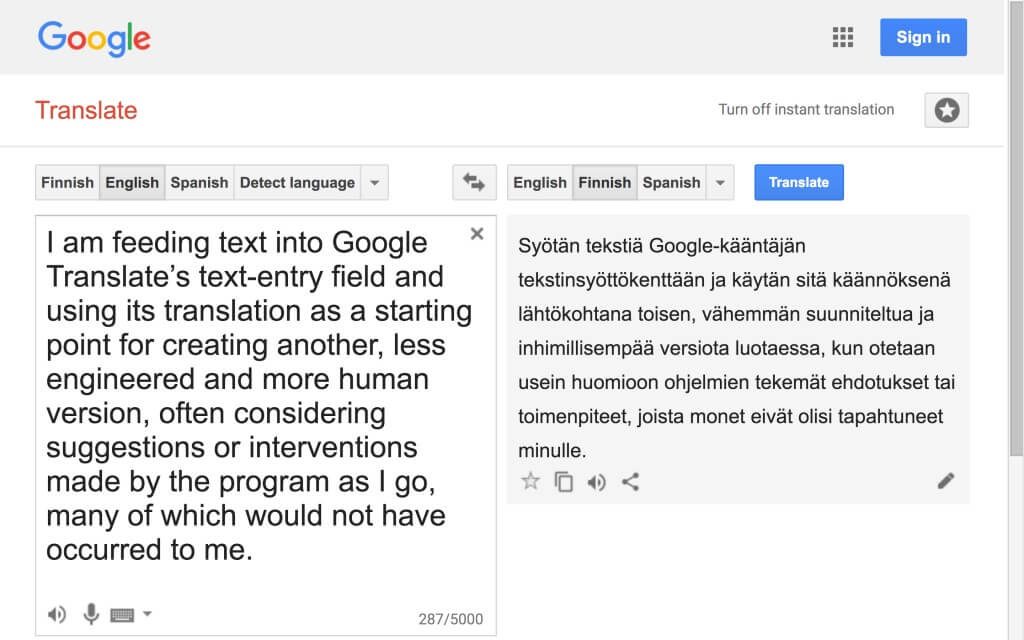

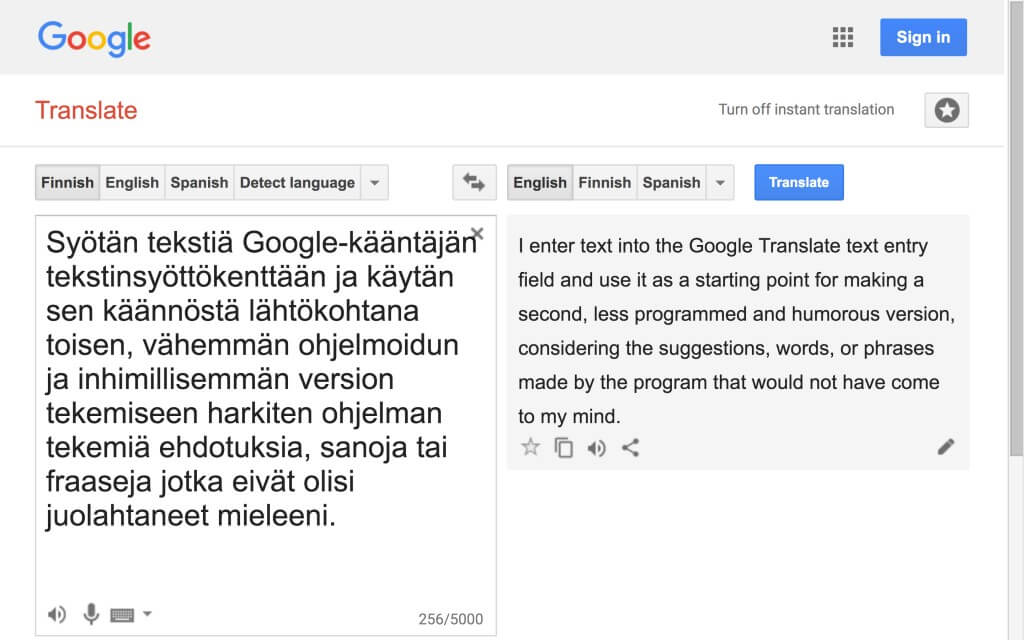

The unceasing change of algorithmic translation is reflected in, for instance, the ways in which the machine translations of An ABZ of Love have changed during the time I have had Google produce them. Compare, for example, Google’s translations from 2010 and 2017 of the following monologue excerpt (from page 69 of the play script):

Rakkauden ABZ, 2008:

Kerro mulle, miks sun jutuissa on aina tällasia ylipitkiä monologeja? Häh?! Ne istuu vielä huonommin leffaan ku sun näytelmiis. Ja niissäkään ne ei toimi läheskään niin hyvin ku sä kuvittelet. Ja aina tää sama kaava: yksinäinen henkilö – useimmiten muuten mies – puhumassa jollekulle poissaolevalle tai vaan osittain läsnä olevalle toiselle. Tilittämässä. Mikä juttu tää oikein on? Onks sulla joku Hamlet-fiksaatio vai mitä?

Google Translate, 2010:

Tell me, why Sun is always desperate for Tallassee lengthy monologues? Huh?! They sit still worse movie ku Sun näytelmiis. And these statements are not working nearly as well-ku sä imagine. Tää and always the same formula: a lonely person – usually the other man – talking to somebody, but absent or in part to the presence of the other. Remitted. What is the correct thing Tää? Do you have a Hamlet-fixation or what?

Google Translate, 2017:

Tell me why the stuff is always overwhelming monologues? Huh?! They are sitting even worse in the movie theater. And even then, they do not work as well where you imagine. And always have the same formula: a lonely person – mostly a man – talking to someone who is absent or partially present to someone else. Being made available. What’s the deal right? Does anyone have any Hamlet fixation or what?

The translation produced by the current system is not in all respects better, as the last sentence demonstrates. However, the new translation is remarkable in that it does not contain any untranslated, spoken language (the play is written in colloquial Finnish). It is precisely these non-translations that burden the 2010 iteration. The overall impression is that the current system is more efficient in producing text that is in the target language—albeit at the expense of translation accuracy (3.5EN3).

How Have We Changed

It is more difficult, however, to definitively say how we, the writers of this research—the performers of love.abz/(love.abz)3, DAR, and myself—have changed with this technogenetic spiral involving algorithmic technologies. I have chosen not to interview the writer-performers of love.abz/(love.abz)3 on their experiences of the psychophysical impact of live writing. For this reason, I can only speak for myself with regards to changes brought about by the incorporation of machine translation and its close partner, speech recognition, into writing processes.

As for my own authorship, I wonder have I, as a writer, become algorithmic—or at least more algorithmic. In other words, have I programmed myself to write more automatically than before. Do I produce text faster? Is the text qualitatively better than before the introduction of new technologies (or techniques)? Above all, have qualitative changes occurred in my thinking? And if so, what is the role of digital media in this change?

These are, of course, questions that I constantly ask myself while writing this thesis. The obvious answer is that I am still a human author. Regardless of how much I interact with writing machines (3.5EN4.5), I will not adopt from them the capacity to write according to any algorithm, no matter how hard I try (3.5EN5). Another question altogether is how algorithmically generated texts and algorithmic features common in digital devices, such as autocomplete, modify the natural languages I use. As Frederik Kaplan points out, programs offered by companies such as Google are not just services—ultimately their purpose is to make language economically more viable, algorithmically more presentable, as it were (Kaplan 2014, 59–60).

Writing “through, with, and alongside”—to recall Hayles’s formulation (Hayles 2012, 1)—the digital media of my choice has led, above all, and perhaps paradoxically, to an increase in both awareness and uncertainty. By this, I refer to a heightened awareness of the mutability, fluidity, and contextual instability of language that constant translation, and especially self-translation, brings about. This awareness is related to the reflection on the nature of textuality at the very beginning of this research project (3.5EN6).

Notes

3.5EN1

As Rita Raley writes, Weaver’s wish, expressed in 1955, is that machine translation would allow for the automated transmission of multilingual texts. Thus, it would promote the availability of texts, not to mention international cultural exchange and mutual understanding—ultimately, the free communication of people around the globe. (Raley 2003, 291)

3.5EN2

Christopher Manning has described neural machine translation (NMT) as “the approach of modeling the entire [machine translation] process via one big artificial neural network” (Neural Machine Translation and Models with Attention 3 April 2017, emphasis in original). Google has replaced its earlier statistical methods with a NMT system of its own, although not in all its language pairs (Lewis-Kraus 2016). Microsoft Translator has also migrated to an NMT system. On its website, the company promises “major advances in translation quality” compared to statistical methods: “Neural networks better capture the context of full sentences [-] providing [-] more human-sounding output” (Microsoft Translator launching Neural Network based translations for all its speech languages 15 November 2016).

3.5EN3

Currently, Google continues to use a statistical method in its translations between Finnish and English instead of the neural method (Google 1 July 2017).

3.5EN4.5

By writing machine, in this context, I refer to a machine with the capacity to contribute to the writing process by providing elements—individual words, phrases, whole sentences—that the human writer would not otherwise incorporate into their text (see 2.7).

3.5EN5

The idea of human algorithmic writing is alluring, as is the idea of an algorithm as a dramaturgical tool, a kind of performance script or score. See 2.6.

3.5EN6

In particular, I refer here to “The Textual Event”, a chapter in Joseph Grigely’s Textualterity—Art, Theory, and Textual Criticism in which he writes about the boundaries of a text, textual instability, and the text as a site of instability: “There is no correct text, no final text, no original text, but only texts that are different, drifting in their like differences” (Grigely 1995, 119).