3.8 Fragment 28

- Fragment 28

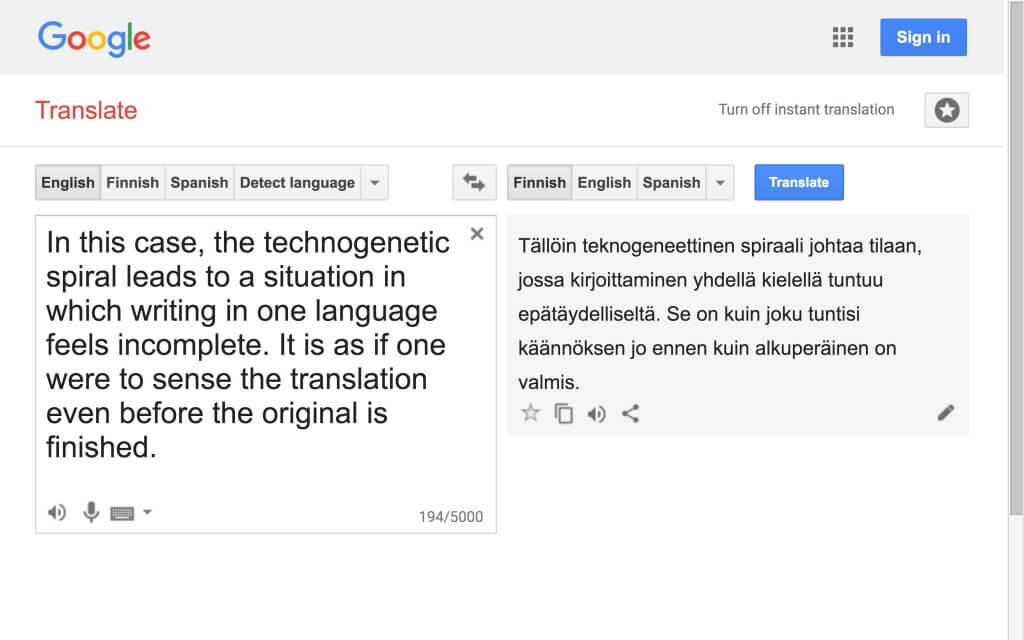

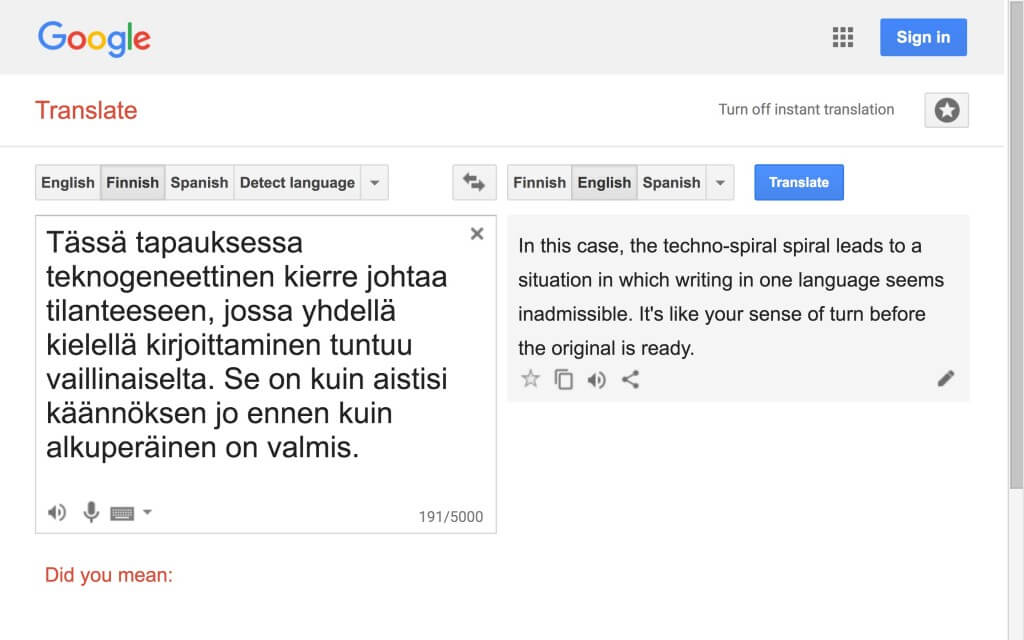

According to Hayles’s hypothesis, technogenetic change occurs through technogenetic spirals, the intensification of the interlacing of humans and technologies. In fragment 28, DAR argues that in this study, technogenic change—or algorithmic adaptation, as I propose to call it—manifests itself as a normalization of bi- or multilingualism. In other words, as a result of the research process, writing in one language becomes the exception, characterized by an experience of lack and the anticipation of translation.

In Hayles, technogenesis is related to anthropogenesis, i.e. hominization, the process of becoming human—recalling Bernard Stiegler’s assertion that anthropogenesis is a form of technogenesis (3.8EN1). Hayles refers to the prevailing consensus among paleoanthropologists that human development is inextricably linked to the development and spread of tools. Coevolution of this kind, involving non-digital tools, can be considered a primary form of technogenesis, in contrast to contemporary technogenesis occurring through digital media.

Hayles points to bipedalism as an example of “continuous reciprocal causation” (Clark according to Hayles 2012, 10), in which rising onto two feet allows the human species to literally grasp new tools, which in turn further accelerates the development of bipedalism. Once an individual has access to new tools, the desire to use them again seems to drive them to modify their behavior, to adapt to the new situation. In this (literally) upward bound recursive development, adopting new tools generates “strong adaptive advantages” that sustain the process of coevolution. (Hayles 2012, 10)

Translation as Internalized Prosthesis

Building on these general observations, we can regard LW and WTCST as forms of writing that have developed from earlier forms in an evolutionary process, the purpose of which has been to better adapt to our new environments. Andy Clark’s idea of “continuous reciprocal causation” would, in this case, materialize in the ways in which we, as a writing ensemble consisting of human and non-human agents, are capable of carrying out tasks that were not possible—at least not on this scale—before the introduction of the technics we currently use. As described in 3.6, my claim is that the possibility of parallel writing and enquiry in two different languages is the “adaptive advantage” or new capacity that is thus produced. So, rather than bipedalism, bi- or multilingualism is the evolutionary leap that is at the core of this theory.

In WTCST, the adaptive change only really becomes tangible when one refrains from the activity that has caused it, that is, from algorithmic self-translation. This is how I understand fragment 28. The changes caused by our engagement with digital media seem to be most palpable when systems are shut down, when we are disconnected from our technical ensembles (see 1.12 and adapted from Hayles passage 10). The anticipation of or longing for translation described by DAR seems to reinforce this perception. When translation has become an experiential norm, an internalized prosthesis, only a new adaptation can restore us to a state where single-language writing is experienced as something other than amputation.

Note

3.8EN1

In “Relational Ecology and the Digital Pharmakon,” Stiegler touches on the impications of digital media for knowledge production: “If anthropogenesis is a technogenesis, with the digital this process arrives at a new stage where the techno-logic of knowledge as such must become central both to the reconsideration of the history of established knowledge in the light of the contemporary moment and to the interrogation of the new forms of knowledge that digitisation brings forth” (Stiegler 2012EN, 15–16, emphasis added).