1.3 Fragment 3

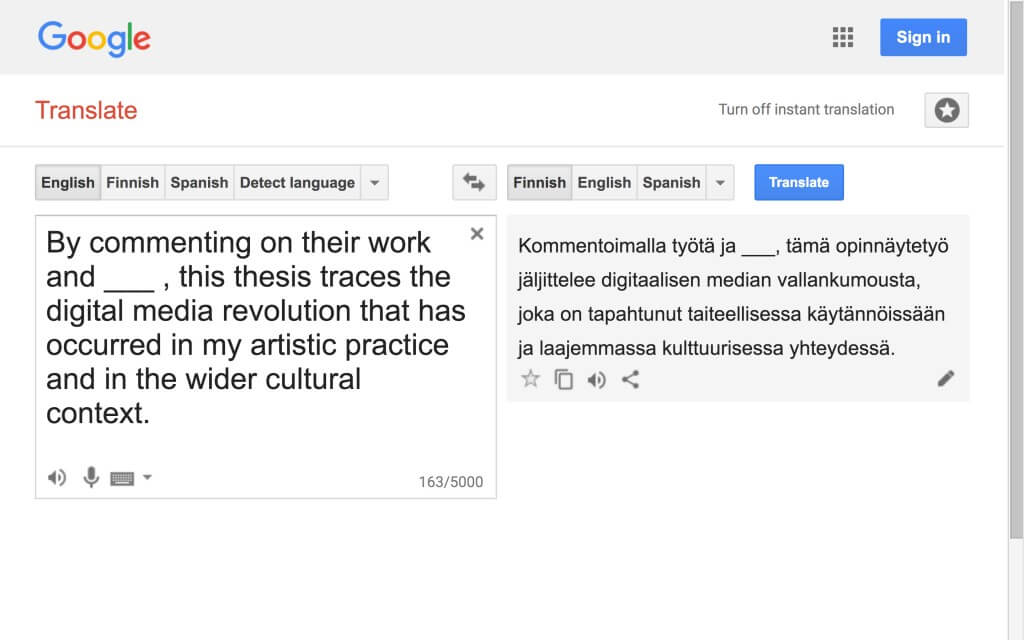

- Fragment 3, adapted from Hayles passage 3

Like the previous fragments, fragment 3 raises many questions. As might be expected, the first questions concern the blank that appears again in this fragment. What other than the work of the artists and researchers not mentioned in 1.2 does the thesis comment on? Or—if we interpret the blank differently—how else than by commenting on the said work does the thesis “trace the digital media revolution”?

Also, how are we to understand the fact that DAR calls their Hayles-adaptation a “thesis”? Is it a thesis within this thesis, an internal version of this work (see 2.6)? In addition, what is the “artistic practice” that DAR refers to? So far, we know only that, one way or another, it has to do with writing, reading, and digital media.

I could go on: what, for example, is the “wider cultural context” that DAR refers to? The world? Instead of demanding answers at this point, however, I will approach the fragment slightly differently. In spite of the many questions, it does in fact also give rise to a few observations. In the following, I will try to focus exclusively on what is written in the fragment—as if reading through a lens that has been zoomed in on an object, leaving everything else blurry or out of the image altogether.

Principle of Translatability

In fragment 3, the tensions DAR faces are plain to see. They seem to propose responding to the artists and researchers not mentioned in 1.2 in and through their practice—as is the common phrase in practice-based research (1.3EN0.5)—in order to strike an institutionally acceptable balance between the demands of the art world and academia. It is noteworthy that DAR uses the verb “comment,” suggesting that what they are writing may be a commentary, a set of explanatory or critical remarks on texts or events that can also be understood as a dialogue between several speakers and/or works (1.3EN1).

In addition to walking a tightrope between the art world and academia, DAR is attempting another balancing act, namely that between their potentially idiosyncratic practice and a wider cultural context—both of which have, according to fragment 3, been changed by the digital media revolution. Again, word choice is revealing. While Hayles writes of “media upheavals” (see adapted from Hayles passage 3), in their rewrite DAR opts for “media revolution” in the singular (see fragment 3). Both “upheaval” and “revolution” certainly refer to change in—or disruption of—the existing order, but the latter term is clearly more political.

If taken for their word, DAR therefore aspires to demonstrate how changes in our media environment have affected their artistic practice and our culture in general (1.3EN2). Here the desire to imitate Hayles’s broad project—which brings together the natural sciences, technology, social sciences, in addition to the humanities—is evident. If the main content of Hayles’s project really is to “explore the proposition that we think through, with, and alongside media” (see adapted from Hayles passage 1), then DAR’s purpose seems to be transfering this content to another context. It is as if they were attempting to translate Hayles’s project into a language of artistic research.

This is a challenging task as not everything is translatable, at least not unproblematically (1.3EN3). The most important methodological principle of this research is therefore translatability. If I can not translate a text satisfactorily, it does not belong here. Translatability, thus, delimits the research, acts as its bellwether. In order to be part of this research, a sentence, argument, or citation must be translatable into its language (1.3EN3.5).

Always Double

Returning to the question DAR poses in fragment 1, on the basis of the first three fragments this much seems clear: while the we pronoun in Hayles points to, for the most part, scholars working within the humanities and especially the digital humanities (1.3EN4), in DAR it mainly refers to practicing artists and artistic researchers. Already on a linguistic level, this difference points to the gap between the projects the two embark on, a gap that DAR seems determined to bridge—rather than acknowledging and accepting it.

This gap is all the more evident when considered against the backdrop of the relationship of practice and theory in artistic research. In “The Power of Deconstruction in Artistic Research,” Michael Schwab deals with this tensional relationship and argues that the biggest methodological problem of this “comparatively recent academic trend” is where artistic research takes place. According to Schwab, the definition of artistic research as research that comprises artistic practice implies that neither practice nor the supporting written component are research in themselves, since only together do they form an artistic research. Artistic research is, therefore, “always double,” as practice and theory reference each other. In his critique, Schwab touches on the methodological freedom of the artistic researcher: “Naturally, such a deferral can be perceived as a problem, because no clear instruction can be given to a researcher as to how he is supposed to orchestrate the relationship between theory and practice.” (Schwab 2008EN, 1)

Notes

1.3EN0.5

See, for example, this description: “Practice-based research, as applied to arts, is research in and through artistic practice and design (for example: fine arts, audiovisual art, design, interior architecture, hybrid forms and interdisciplinary work) where the researcher’s own practice and critical engagement are integral to the research subject, processes and outcomes. In a doctorate practice-based research, the researcher must therefore demonstrate a high level of artistic creativity, imagination and skill in order for the doctorate to make a substantial and original contribution to knowledge, understanding and art practice.” (Phdarts.eu 1 February 2017, emphasis added)

1.3EN1

The current degree requirements of the Performing Arts Research Center (Tutke) specify that a doctorate comprises artistic parts and a commentary subject to external examination. In the requirements, the commentary is defined as follows: “The commentary is aligned with the artistic parts, and it justifies the aims and methods of the doctoral research with respect to the research and practices of the field explored.” “The commentary shall demonstrate an ability to analyze, articulate, conceptualize and theorize the artistic designs of research, and to contextualize these in ways that are characteristic of artistic research.” “The doctoral research commentary shall present the aims, methods, structure and results of the research.” (Uniarts.fi 1 February 2017)

1.3EN2

I refer here to cultures possessing contemporary technology, in which digital media are widely in use.

1.3EN3

The Dictionary of the Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon, an “encyclopedic dictionary of close to 400 important philosophical, literary, and political terms and concepts that defy easy—or any—translation from one language and culture to another,” attests to this very point (Cassin et al. 2014).

1.3EN3.5

Translatability refers to a possibility or potentiality, to a capacity rather than an existing reality, as do the other nouns formed with the suffix -ability (-barkeit in German) in Walter Benjamin’s work, as Samuel Weber points out in Benjamin’s -abilities. The two other main -abilities as discussed by Weber are “citability” and “reproducibility,” as in “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.” (Weber 2008)

1.3EN4

A concise definition of digital humanities is “work at the intersection of digital technology and humanities disciplines” (Drucker 2013EN).