1.4 Fragment 4

- Fragment 4. In what is perhaps a sign that DAR is getting bolder as they continue to adapt, fragment 4 is the first to not relate directly to any one passage in Hayles’s book (n.b. the absence of a link to a correlating passage here). Also, it is the first fragment without any blanks.

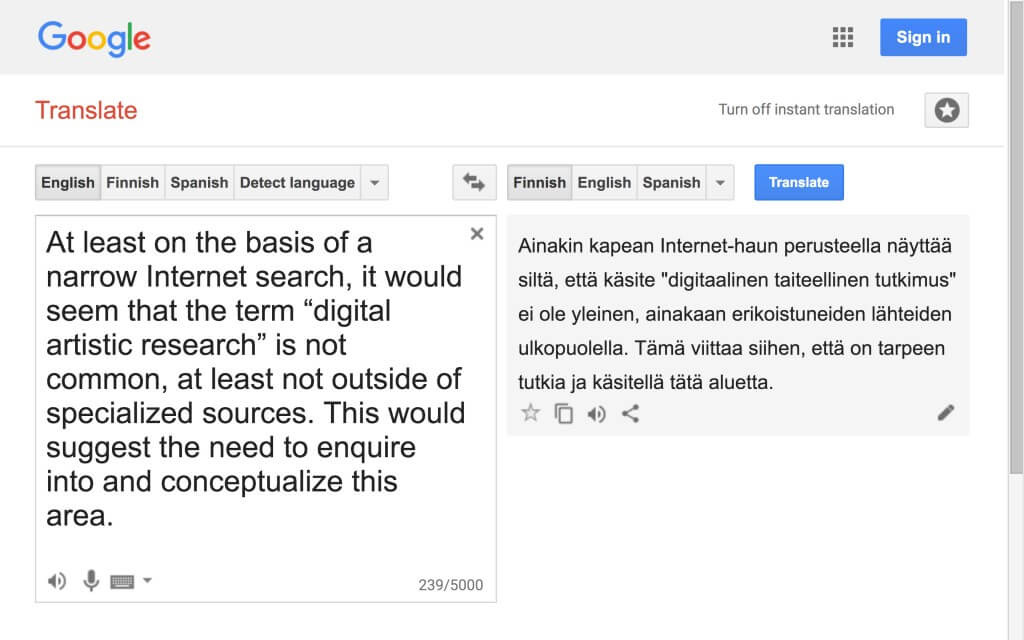

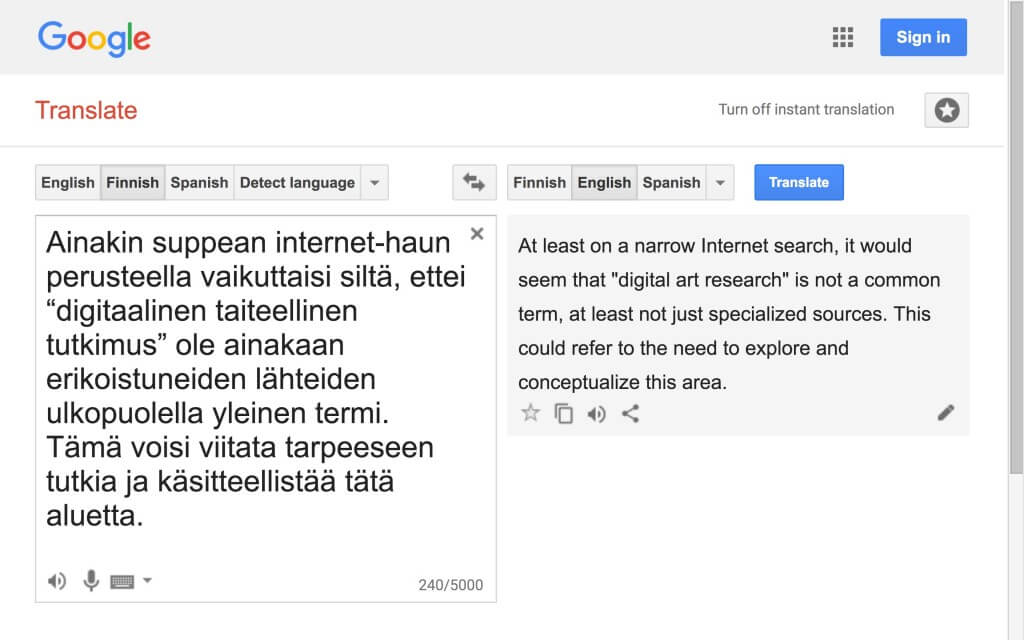

If the task of the academic researcher is to first identify a lack of research in the field and then to contribute to replacing that shortage with new, justifiable knowledge, then in fragment 4 DAR seems to gesture toward enacting this task in their research to some degree. In fact, in fragment 4 DAR justifies the need for this research by demonstrating that “digital artistic research” (incidentally also DAR) seems to be a rare term. It is therefore necessary to examine and conceptualize this area. By DAR’s own account, the argument is based on “a narrow internet search,” which may have not reached the “specialized sources” that remain undefined in fragment 4 (1.4EN1).

DAR would seem to suggest that more extensive searches would produce similar results: both in and outside of the field, digital artistic research is a largely neglected area that deserves to be examined in this work. If we, at least for now, accept DAR’s argument—and the somewhat questionable evidence it is based on (1.4EN2)—we can move on to ask what digital artistic research actually means.

Digital Media as Sites of Research

Here, I turn to Hayles. One of her main theses, to be specific, is that the humanities use digital media for research purposes in two significantly differing ways. Increasingly common is publishing research results in digital form, in which case digital media replace more traditional forms of print publication. In addition to this basic level of engagement with the digital, Hayles explores practices of another kind: those in which digital media are used as means for carrying out the research itself, as research sites. (Hayles 2012, 2–9)

Although Hayles, for good reason, values digital publishing, the main focus of her project is clearly in the latter possibility, in considering how digital media can be used to enhance the actual doing of research. In fragment 4, DAR would seem to take a step in the same direction, guided by Hayles, opening the question how artistic research could be realized in digital media. Also for DAR, mere publication of artistic research—and this research in particular—is hardly enough. The gesture is significant, even if its execution is faulty, since it points to how digital media are approached in this research—in other words, what the nature of their instrumentality in this context is.

As an example of artistic research that utilizes digital media in its very implementation, I mention here Tuomo Rainio’s research exposition “Reconfigured Image—translations between concept, code and screen.” A visual artist, Rainio presents the viewer of his online exposition with a gallery-like virtual space in which he has juxtaposed images and text. The viewer navigates through the black, complex assemblage of Rainio’s digitally created and/or manipulated images using a map-like structure. The texts—in which Rainio refers to other artists, philosophers, and writers—comment on or extend the still and moving images, chosen from Rainio’s prior exhibitions. The exposition creates a (also technically) challenging, intricate digital space that although being in a state of constant change still allows the viewer to contemplate Rainio’s striking images and his (textual) reflections on the nature of being of digital images, among other questions. (Rainio 2015)

Paraphrase/Imitation

As fragment 4 does not correspond to any particular Hayles passage, it offers an opportunity to continue reflecting on what exactly DAR is doing. In the fragment, DAR clearly deviates from their plan to adapt each and every sentence of Hayles, which I allude to in , to make observations more loosely based on the book. The obvious conclusion is that DAR’s adaptation consists of two types of fragments: some more, some less directly based on Hayles. It is also noteworthy that if DAR’s adaptation is indeed a commentary, as I suggest in 1.3, then what I am writing is a commentary of a commentary (1.4EN4).

Rather than presenting my assessment on how many layers of commentary this thesis may comprise, however, I would like to turn to translation studies for some conceptual assistance, as I also do in 3.6. The term paraphrase comes from the Greek paraphrasis, in which the para-prefix expresses modification. Phrazein is to tell, so to paraphrase is to tell in other words. This would seem to describe quite accurately what DAR is doing: telling in their own words and in their own context what Hayles has expressed in her book. In fact, DAR’s writing could be seen as a practice of paraphrasing, such is the determination with which they go about doing it.

In translation studies, paraphrase is classified as a form of intralingual translation (Jakobson 1971, 233), or as a way of translating that is in between word-for-word literalness and “free” translation. In John Dryden’s 17th century classification paraphrasing refers to translation in which the translator is given creative liberty, as long as the meaning of the original text is conveyed. (Bank of Finnish Terminology in Arts and Sciences 27 July 2017: Käännöstiede: parafraasi) Here the term becomes more problematic in relation to DAR. In what sense and to what extent can the meaning of Hayles’s book be seen to be conveyed in DAR’s adaptation of it? Can DAR be seen to refrain from taking such liberties that would warrant calling their adaptation something other than a paraphrase?

Certainly, DAR’s adaptation cannot be considered a metaphrase or literal, word-for-word translation. Dryden’s third category, imitation, would instead seem best suited to describe DAR. In Dryden’s view, imitation occurs when a translator exercises the freedoms of a writer and makes changes to both form and content, in other words to the very meaning of the original. (Bank of Finnish Terminology in Arts and Sciences 27 July 2017: Käännöstiede: parafraasi) Rather than a practice of paraphrase, then, DAR’s writing can be regarded as a practice of imitation, in which they mimic Hayles’s gestures, modifying them for their own purposes (see 1.12). In my remarks, I try to benefit from the distance I have from this imitation, though my contribution to this thesis may ultimately also be imitation—if not imitation of imitation.

Notes

1.4EN1

Such sources could, for instance, be the field’s online publications—the Journal of Artistic Research (JAR), which published its first issue in 2011, and RUUKKU Studies in Artistic Research, which followed in 2013, to mention a few—in which the use of digital media in artistic research is often represented very differently.

1.4EN2

The claim is based on a simple internet search, made using Google’s search engine, that produces only four exact matches for the words “digital artistic research” (the same words translated into Finnish produce no exact matches). Of the results, three are at least vaguely relevant to artistic research. The search is repeated several times during the writing of this thesis.

1.4EN4

In philology, a commentary is a linear explanation of a text that proceeds “line-by-line or even word-by-word,” an informational parallel text. For the sake of this study, it is interesting to note that commentaries are generally considered to utilize close reading, which is discussed both in Hayles and in this thesis (see 2.2). In this context, it is essential to ask how a commentary based on hyper or machine reading differs from one based exclusively on close reading. (Wikipedia 27 July 2017)