3.4 Fragment 24

- Fragment 24

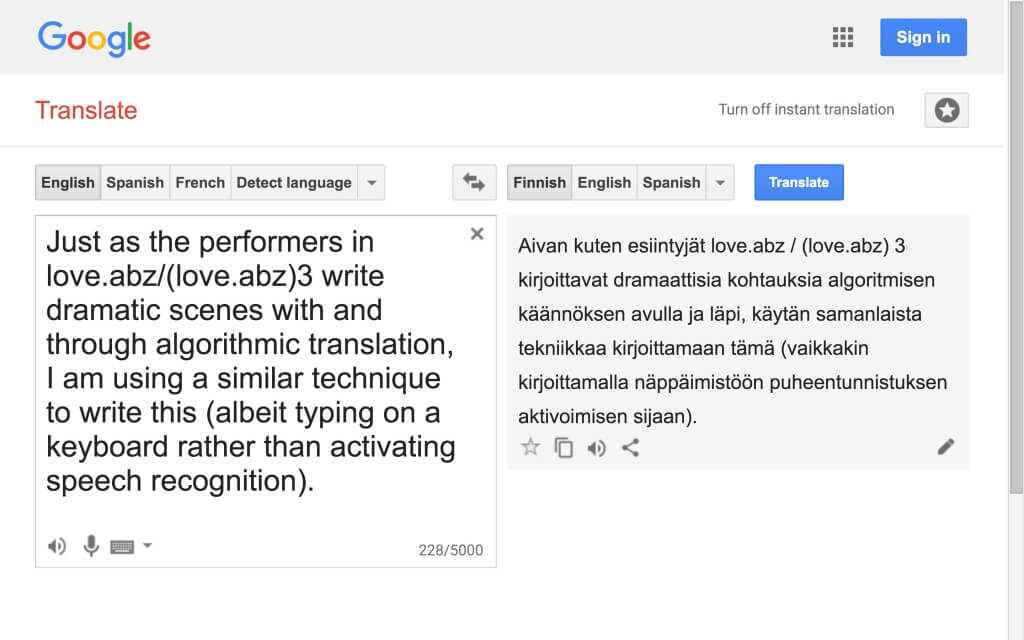

In this response to fragment 24, I will describe (love.abz)3, the second artistic part of this research. My reason for intervening in this way is an awareness of the lack of visibility that (love.abz)3 has, thus far, had in this thesis. Until now, the artistic parts have almost without exception been dealt with together, as if they were a uniform whole. However, this is not the case in all respects. By changing the internal textual relations of the performance and deconstructing the live writing method introduced in love.abz, (love.abz)3 brings to the broader project a qualitatively different and heightened variation of live writing. In doing so, it contributes to the development of the writing methods discussed in 3.6 and alluded to in the latter part of fragment 24.

Second artistic part: (love.abz)3 (Theaterdiscounter, 2015)

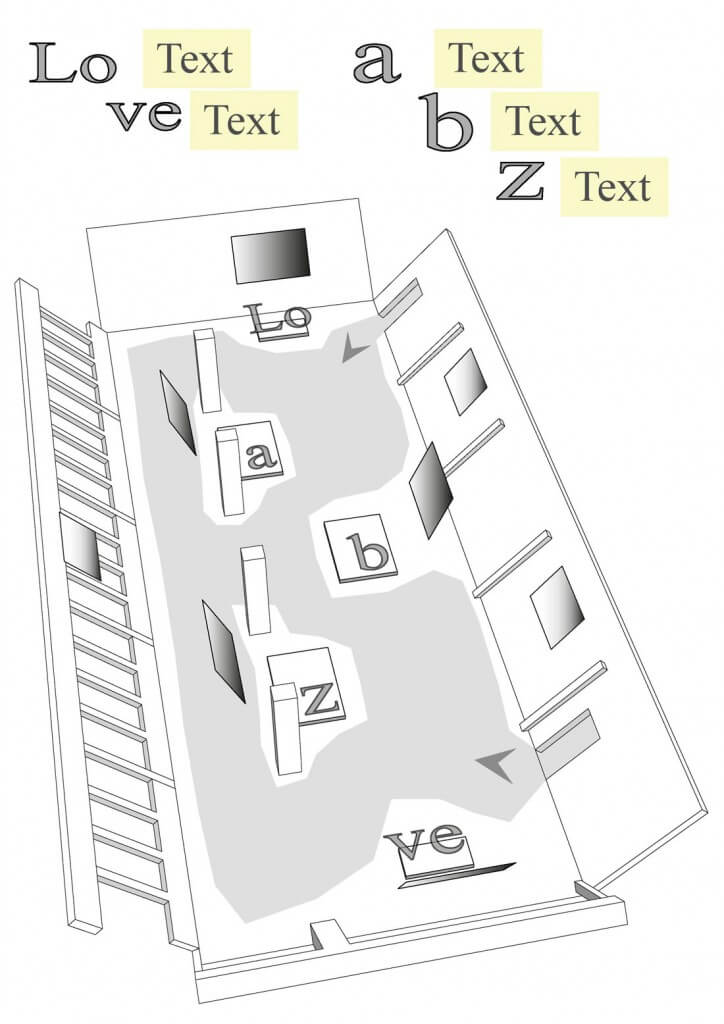

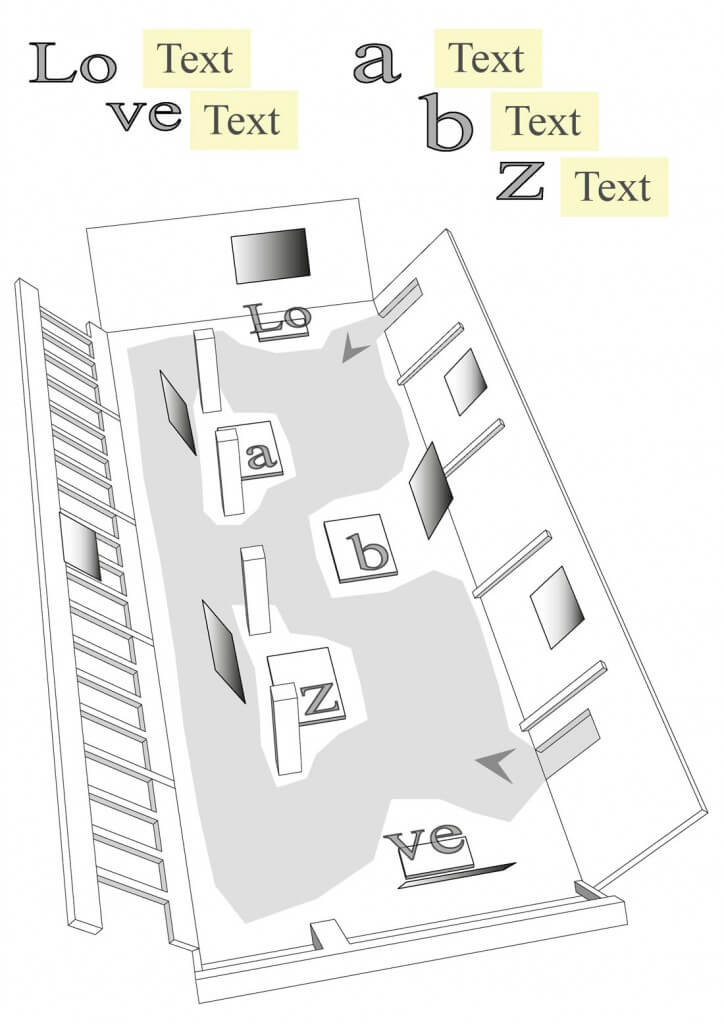

Performed five times in Theaterdiscounter, Berlin, in November 2015, (love.abz)3 brings together eleven performers, three of whom have already performed in love.abz (see 2.2). We divide Theaterdiscounter’s elongated, rather low performance space into five independent workstations that are not, however, isolated from each other by walls or in any other way (see fig. 3.4.1). The workstations are named after the letters in the title of the performance: LO, VE, A, B, and Z. At workstation LO, a performer works alone writing prose in English, Finnish, and German using a keyboard. (As in love.abz, this performer also closes the performance by selecting a passage from their prose for a synthetic voice to read.) On the opposite side of the performance space, at the other end, there is workstation VE, where I perform random draws that determine the dramaturgy of each round of writing (three in all per performance).

- Fig. 3.4.1 Sketch of (love.abz)3 workstations. Image: Johannes Maas.

Workstations A, B, and Z are located in between LO and VE. Two of them (A and Z) face the audience passageways, while the third (B) faces in the opposite direction (see fig. 3.4.1). In these three workstations, the nine main performers stand on podiums, three performers per podium. Each performer has a microphone of their own that stands in front of them on the podium. Each workstation has identical video projections, behind and in front of the performers, from which both the audience and performers follow the writing processes in real time. Workstations LO and VE are also equipped with video projections for the audience to follow the progression of the prose (LO) and the random draws (VE).

When the doors are opened, all nine main performers exceptionally stand on the workstation B podium. They produce reference material (voice samples) for the speech recognition software Dragon Dictate by taking turns reading, in German, the texts that appear in the projection (see video 3.4.1). Some of the performers do not speak German, which is why this calibration phase is particularly challenging. There is no fixed auditorium in the space. The audience roams or sits on the few wooden benches placed in front of workstations A, B, and Z. While the main performers present the calibration texts in a relatively theatrical manner (e.g. whispering, shouting, singing), the prose performer begins his work, which, with the exception of a few pauses, continues uninterruptedly throughout the ninety-minute performance.

Video 3.4.1. See also (love.abz)3 production info. Video: Andrea Keiz

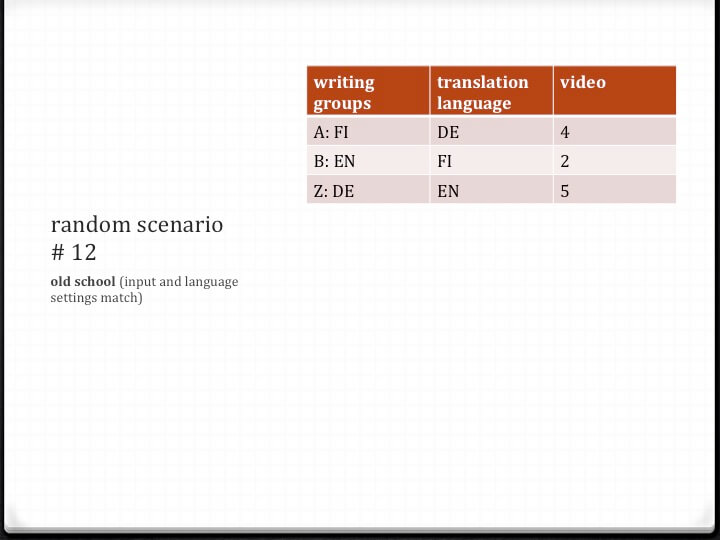

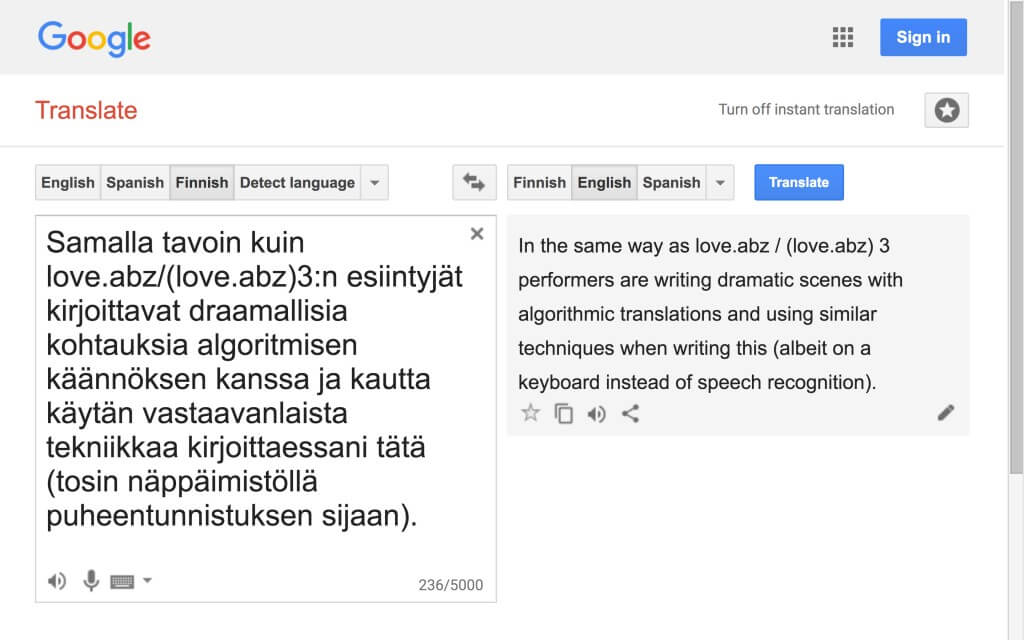

Calibrating the software takes about ten minutes. Once the process is completed and the computer starts processing the performer’s voices, all nine main performers gather around workstation VE. I go to the podium and type the words “Round 1, Random Draw, Old School” into the text-entry field of the Google Translate webpage. Google’s synthetic voices read the text and its German translation. I then navigate to the Random.org website and its “True Random Number Generator.” With this program, I generate numbers that determine the following factors for the first round of writing: 1) the workstation of each group; 2) the translation language, i.e. the language that Google Translate will translate the group’s writing into; 3) the stimulus texts used by each group.

Textual Relations

Importantly, the stimulus texts used in (love.abz)3 are not the looped scenes of An ABZ of Love, as in love.abz, but rather texts created by the performers themselves in rehearsals. A slight textual connection to my play, however, still exists in that I have asked the performers to create the stimulus texts based on dramatic situations extracted from the scenes of my play. Consequently, in this stage of the process the performers have translated dramatic situations rather than texts. More specifically, I have given them brief descriptions or prompts—such as “your partner forbids you from bringing a toothbrush over to their place”—that I have abstracted from the scenes of my play. From these prompts, the performers have produced text using the live writing technique in rehearsals. They have then shortened and, if necessary, made the texts more anonymous for performance.

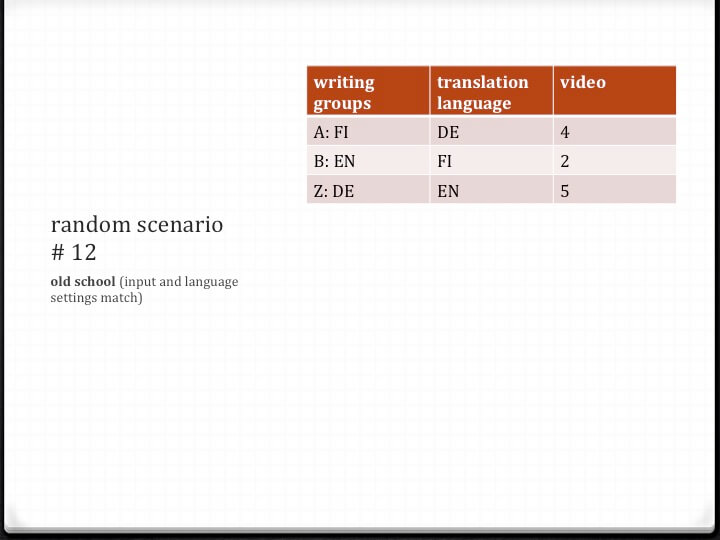

In the first two rounds, the groups write in Finnish, German, and English according to the language skills of the group members. The composition of the groups is predetermined. Once the random draw for the first round is complete, I display a slide with all of its results (see fig. 3.4.2). We have named the first two rounds of writing “old school,” as they mainly follow the live writing technique established in love.abz—albeit with the significant exception that instead of one group there are three groups writing (and reading) simultaneously. The performers disperse to their assigned workstations. All three groups first tell the audience something about how the texts have been created (free speech). After that, the groups read the stimulus texts by themselves rather than in collaboration with synthetic voices, as in love.abz. Once they have finished reading, the members of each group confer amongst themselves, coming up with a situation for the scene they are about to write (who, where, when, what) (see 1.8 sample 3). Each performer adjusts their egg timer to alert in three minutes. Using either Dragon Dictate (for English and German) or Siri (for Finnish) as speech recognition engine, the performers start writing into the Google Translate text-entry field, taking turns speaking into their individual microphones.

- Fig. 3.4.2 Example of random draw results for “old school” writing.

When a performer’s egg timer sounds, they step back and watch the remainder of the improvisation from there. When the third performer in a group has stopped writing, the group looks to the other groups and either goes to watch the other groups work (if they are still working) or waits for the other groups to come to their workstation (if they are the last group to have finished writing). When all the performers have gathered around the last group’s workstation, the members of this group are asked three questions using the Google Translate synthetic voices: 1) please describe what you just read (stimulus text); 2) please describe what you just wrote (improvised text); 3) please tell us what you are going to read next. The members of the group decide on whether they read the text they have written or its translation.

When the group has answered the questions, it reads the text it has chosen. The text that the group has chosen not to read is then read by speech synthesis. (The only exception to this is texts in Bulgarian, for which we do not have speech synthesis.) When the synthetic reading ends, the group that has finished second to last returns to its workstation. The other groups follow it. Precisely the same procedure is repeated at its workstation with the questions, choices, and readings. Finally, the same procedure is repeated at the workstation of the third group. When the synthetic reading of the third group is over, all the performers again gather around workstation VE. I perform the random draw for the second round and the procedure described above is repeated with identical structure but different variables (workstations, translation languages, and stimulus texts).

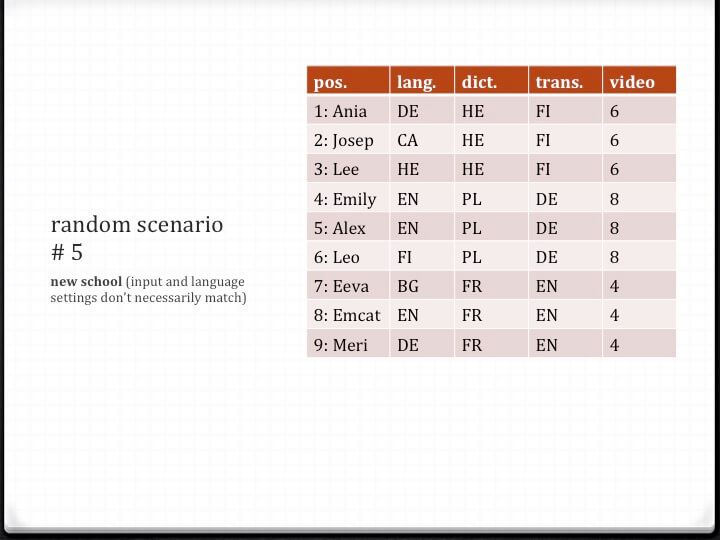

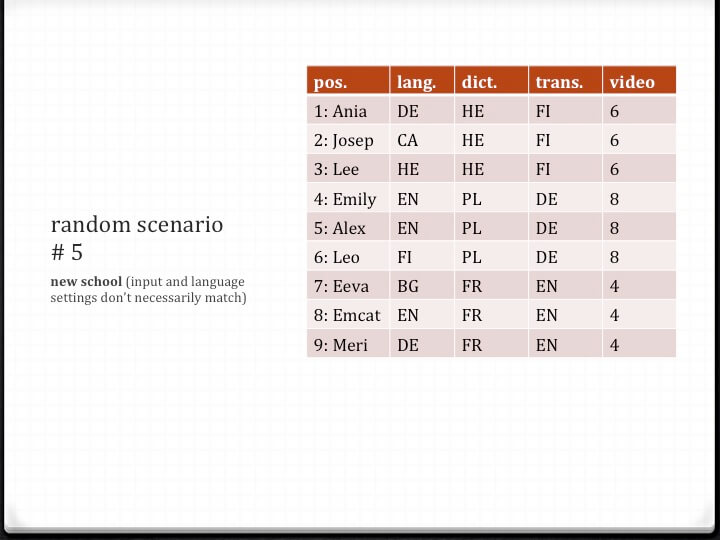

When the second round of “old-school” writing is completed, all the performers gather once again around workstation VE. There, I perform the random draw for round three. This time, however, the draw is not carried out with the help of digital tools, but rather analogue ones (resembling the draw used in love.abz). Returning to the podium, I take a brown paper bag with the words “THIS IS MY PLAY” on one side of it and “PLEASE CHOOSE ONE” on the other. I then show the audience thirteen laminated tags, each corresponding to a “new school” scenario. I put the tags in the paper bag and shake it. Next, I approach an audience member that I have chosen for unspecified reasons, open the paper bag for them, and ask them to take a tag out of the bag. I thank them and return with the tag to my workstation. There, I open a computer file that corresponds with the tag. The document contains the following information: 1) writing positions for all nine main performers (this time individually, not by group); 2) writing language for each individual performer (one of eleven possible languages); 3) dictation language (software language setting); 4) translation language for each workstation (i.e. the target language in Google Translate); and 5) stimulus texts for each group (see fig. 3.4.3).

- Fig. 3.4.3 Example of random draw results in “new school” writing.

Deconstructing Live Writing

When the performers have taken in the information, they disperse to their assigned work positions. “New school” writing differs in many ways from the “old school” writing method of the first two rounds (and love.abz). First, the performers no longer write in the predetermined groups (unless, of course, the random draw happens to bring together all the members of a prior group, which does not happen in any one of the five performances). Second, although each workstation is assigned a dictation language, the performers may not be speaking in that language (because they have been assigned their own writing language). In other words, the language used by the performer does not necessarily correspond with the language setting of the software. Third, the performers in one group do not necessarily speak the same language. For example, it is possible that one performer speaks Finnish, the second Polish, and the third Czech, while the software’s language setting is Swedish.

In all other respects, the dramaturgy of the third round of writing is exactly the same as in the first two rounds. The results of “new school” writing, however, are anything but similar. Confronted with up to three foreign (i.e. unprogrammed) languages delivered by three different voices, the speech recognition software is given an overwhelming task. Instead of ceasing to produce text, however, it inevitably continues to do so as if it were to recognize the unprogrammed language(s) (cf. 1.8 sample 4 and video 2.2.1 EN). Unable to find the statistically most likely matches for the words uttered in the foreign languages, the speech recognition algorithms seem to search for phonetically similar words in the language it knows. In this blind translation process, there is no place for meaning, as it involves trying to carry phonetic rather than semantic structures from one language to another. The result is, again, impenetrable text, motley non-language as in the last monologue of love.abz, only now even more so, exponentially more. In the last part of (love.abz)3, the artistic parts of this research are closer to the dispersion of languages described in the Biblical myth of the Tower of Babel than at any other time (3.4EN1). In this deconstructed form of live writing, the research listens, for a good while, to meaning being replaced by noise.

Notes

(love.abz)3 production info

Working group: Otso Huopaniemi (concept and implementation), Josep Caballero García (performance), Emily Gleeson (performance), Leo Kirjonen (performance), Meri Koivisto (performance), Alexander Komlósi (performance), Lee Meir (performance), Teemu Miettinen (performance), Ania Nowak (performance), Eeva Semerdjiev (performance), Annett Hardegen (production), Johannes Maas (spatial and lighting design), Roni Katz (assistant director), Robert Wolf (technical support),

Venue: Theaterdiscounter, Berlin

Performance dates: 13–17 November 2015

Languages: Finnish, English, German, Catalan, Hebrew, Bulgarian, Polish, French, Spanish, Swedish, Czech

Supported by Kone Foundation, Finnland-Insitut in Deutschland, the Berlin Senate, the Finnish Cultural Foundation Central Fund, Fonds Darstellende Künste (Germany)

3.4EN1

The video below, entitled “Babelian Performance,” is an adaptation of two texts that deal with the Tower of Babel. The texts are the English translation of Jacques Derrida’s “Des Tours de Babel” and Samuel Weber’s “Translatability II—Afterlife” (Derrida 2007, 191–225; Weber 2008, 79–94). I complete the 23-minute video soon after the second artistic part and it reflects the Babelian character of its last part.