3.1 Fragment 21

- Fragment 21, adapted from Hayles passage 17

In fragment 21, the first fragment of the third part of this four-part thesis, the Digital Artistic Researcher (DAR) returns to the relationship of the artistic parts and the written part of this research, a topic already touched upon in 1.3 and 2.1. In the preceding fragments of their Hayles adaptation, they have spoken mainly of the central role digital media play in the artistic parts. Here, DAR wants to complement this examination with a broader look at the ways research is conducted in and through digital media in this project as a whole.

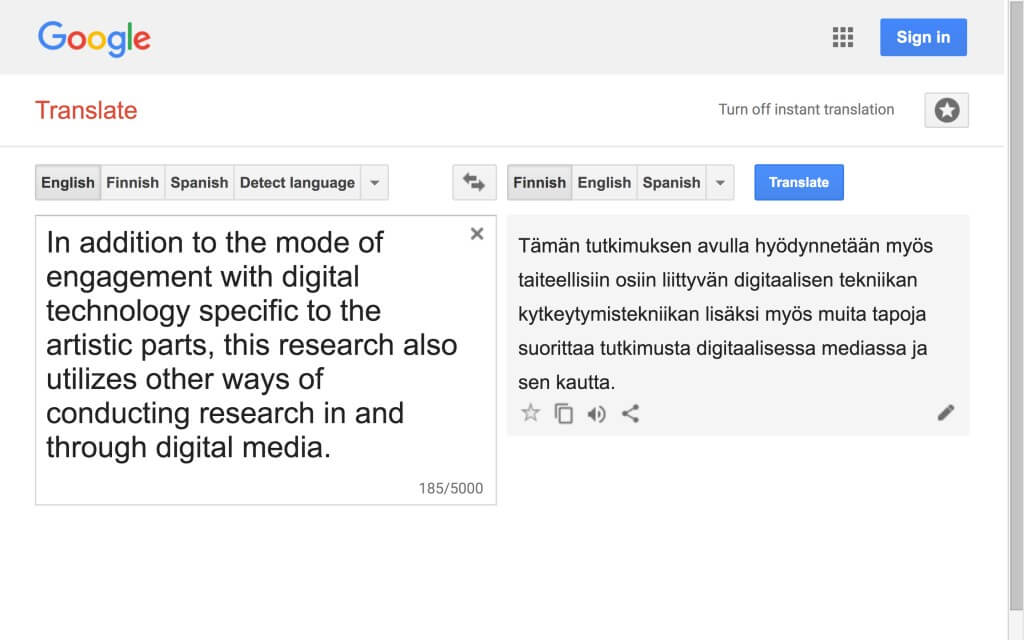

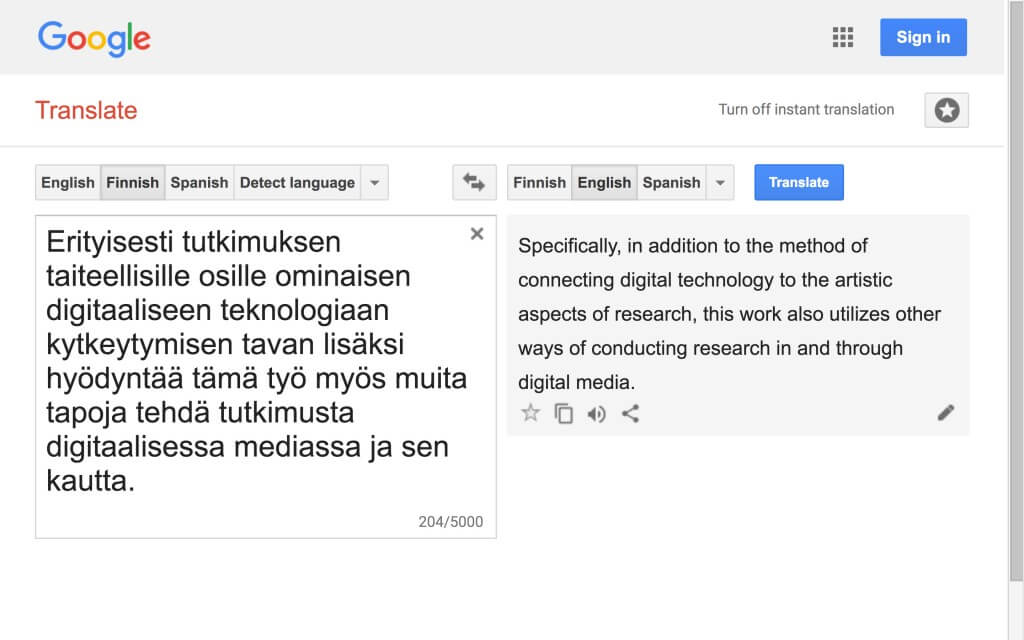

For one thing, this entails recognizing that machine translation—and the Google Translate website in particular—functions as a medium of research here, as well as a platform for the writing happening in both the artistic parts and in this written part. However, before going that far, I will unpack fragment 21 somewhat more gradually. What I take to be its purpose is pointing to how the commitment to digital technology, common to all parts of this research, is varied in this bilingual, open access thesis. (By “other ways,” DAR must be referring to this thesis, as there are only two parts to this project, the artistic and the written.)

Whereas Hayles, in her corresponding passage (see adapted from Hayles passage 17), speaks of a shift from standard to more sophisticated uses of digital technologies, DAR uses this opportunity to speak of another shift, one happening within this particular project: the shift from the art works to the written work. Rather than function as a final report or supplement that simply looks back at the primary parts of the research, the performances, this written part continues the research process by utilizing the same technologies in differing ways (see 2.1). However, the relationship is complex, as the written part continues the research process and yet is temporally and spatially separated from the artistic parts.

There is a tension between smoothing away and reinforcing the boundaries between the different parts, particularly tangible in a project in which both center on writing (see 1.3). Furthermore, the relationship is complex because the written part strives to place the artistic parts in a wider context. There, they can continue their work in dialogue with texts that comment on or analyze them without being subordinate to them.

Speaking to this point, Dieter Lesage suggests understanding supplementarity as an aesthetics and an artistic strategy:

“One should stress the difference between the supplement to the artwork as an academic requirement for having the right explanation on the one hand and a certain aesthetics of the supplement which is inherent in the work of many artists on the other, where the supplement is not seen as the explanation of the work, but rather as constitutive of the work itself. This artist’s supplement is not what gives us the solution, the answer, the right interpretation, but rather what postpones the solution, the answer, the right interpretation even more. So ‘supplementarity’ can also be defined as an artistic strategy to escape the closure of interpretation, to leave all interpretations open, or to make interpretation even more the complex issue it always already is.” (Lesage 2013, 149)

Also in digital artistic research, it is necessary to be able to produce discursive text, to bring one’s research forward discursively. The mere use of “media,” as if language were not a medium, is not enough. However, in the context of this study, the idea of supplementarity formulated by Lesage could mean that this written part only offers partial closure or coverage of the artistic parts and postpones their “final reading.”

In other words, this written part provides a rough, partially machine translation of the artistic parts that awaits post-editing, i.e. the part of the translation process in which a human checks and corrects the machine translation. Much still needs to be done to finish even this rough translation, however. If what is common for both the artistic parts and the written part of this work is that they conduct “research in and through digital media,” as DAR writes, the difference is this: whereas love.abz/(love.abz)3 proposes a way of carrying out and looking at digital, performative writing in the context of stage performance, this thesis correspondingly proposes a praxis and concept for artistic research writing.

LW and WTCST

The artistic parts put on display what I propose to call live writing (LW), while the written part demonstrates and reflects on writing through contemporary self-translation (WTCST), one of the main topics of this third part of the thesis (see 3.6). Primarily, the focus so far has been on LW, which is why this third part takes up WTCST. In short, WTCST is continuous and simultaneous back and forth translation between two (or more) languages carried out by a single artist-researcher utilizing machine translations as rough drafts, material, or reference points.

As both texts are created at more or less the same time, they continue to influence and shape each other until the potential for “cross-fertilization,” as Rainier Grutman calls it, is exhausted (Grutman 2011, 257). Thus, WTCST is a process of writing two parallel texts that differs significantly from a translation process in which original and translation retain their fixed positions (whether or not the translator is the author of the original). Writing in two languages at the same time is, above all, a way of thinking and conducting research; a methodological approach that creates space for reflection that is not merely linguistic by nature.