1.5 Fragment 5

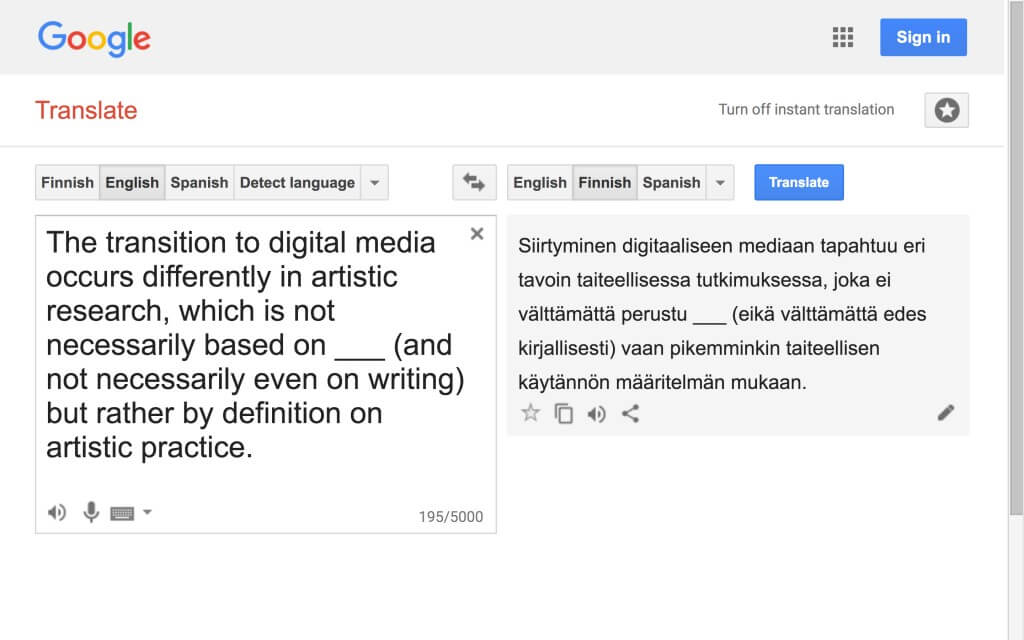

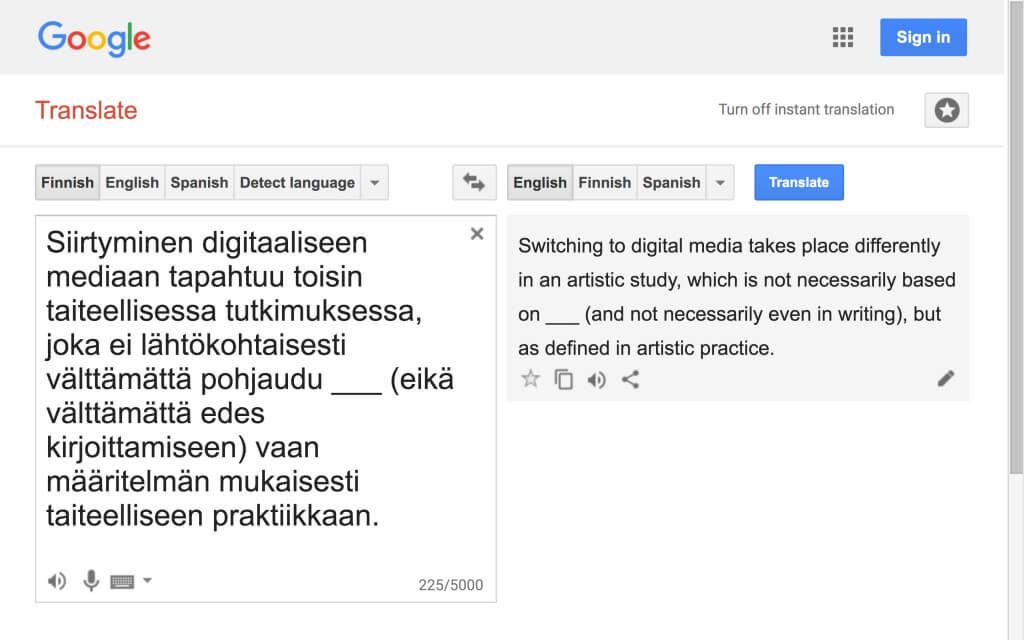

- Fragment 5, adapted from Hayles passage 4

From my privileged position in between DAR and the reader-viewer, I see that, in fragment 5, DAR sheds light on the particular position artistic research holds in the technological change under discussion. As a hybrid, multimedial, and multimodal domain, artistic research complicates the sharp dichotomy between print and digital—which is one of the potential pitfalls of digital humanism—, as DAR rightly implies (1.5EN1). Bringing together a wide array of different artistic practices including but not limited to music, visual arts, dance and theater, artistic research is not, in principle, dependent on print in the same manner as literature, philosophy, and many other areas of the humanities (1.5EN2).

Also, artistic research by definition complicates the privileged position of discursive writing as the foremost mode of carrying out research and distributing its outcomes (1.5EN3). Instead, it proposes a twofold model as described by Schwab in which writing and artistic practice share the work of research (see Schwab 2008EN and 1.3). This model is further complicated by projects such as the current one, in which writing is a central part of both discourse and artistic work (see 1.10). This is one of the reasons why elements from my artistic practice (translation images, video texts) encroach on this written part of the research, interrupting its linear course and presenting writing of another kind. Similarly, I have used research texts in the artistic works—the leakage is bilateral.

At least in principle, there are comparatively few barriers for the artistic researcher wanting to fully engage with digital media as means of not only distributing but also conducting research. It is at least an apparent truism to state that if research happens in and through live art, for example, digital media may well provide more effective means (video, audio) of reflecting upon or commenting on the work. One need not be an expert in the humanities or qualitative social sciences—not to mention the manifold artistic fields artistic research comprises—to see how shifting from print to digital is different within artistic research compared to these fields. If they so desire, an artistic researcher can choose a research question emerging from a digital realm and remain in that realm throughout their research. This is the possibility the model of digital artistic research I propose points toward.

Textual Subordination

However, rather than expanding on the point I outline above, I turn now to the subordinate position DAR seems to hold in this thesis. DAR makes arguments, delivers what is in effect a monologue, the adaptation (1.5EN4). For my part, I comment on and present observations on DAR’s arguments, in addition to making arguments of my own. In this textually multi-layered arrangement, DAR is prohibited from commenting on my comments, from responding. Thus, their monologue remains just that, a monologue, as if they were—in accordance with dramatic convention—speaking alone, seemingly unheard by other characters.

DAR’s room for maneuvering is limited to the translation boxes (screen captures), the textual stalls of sorts that are located at the top of each section of this thesis. This one-sided, hierarchical structure reduces the dialogical potential of my commentary (see 1.3). It may also, to some extent, reflect my relationship with the writer-performers that perform in the artistic parts of this research.

Video 1.5.1 EN NB: The reference Raley 2017 in the video is incorrect. The correct reference is Raley 2018.

Notes

1.5EN1

DAR does not specify which disciplines they compare artistic research to in fragment 5. However, in light of the corresponding Hayles passage, it is reasonable to assume they are referring to the humanities and qualitative social sciences (see adapted from Hayles passage 4).

1.5EN2

The blank that appears in fragment 5 has, by all accounts, to do with the difficulty of finding a satisfactory and working Finnish translation for the versatile English word “print”—and specifically in the sense Hayles mainly uses it in, as the opposite or counterpart of digital media. “Painokulttuuri”, “painotuotekulttuuri”, “painotekniikka,” and “painettu sana” are all relatively cumbersome approximations of the concise “print.” With these restrictions taken into consideration, the blank is most likely to disguise the words “assumptions, presuppositions, and practices associated with [print].” (Hayles 2012, 2)

1.5EN3

Highlighting the topicality of the debate on the relationship of artistic practice and writing, the Society for Artistic Research organized an entire conference on the topic in 2016. Entitled “Writing as Practice, Practice as Writing,” the conference set out to explore “how both writing and practice operate as ways to convey new knowledge, understanding and experiences by which we (re)organize our lives.” On the conference website, the organizers describe the relationship of writing and practice within artistic research as follows: “Often the relationship is felt to be one of friction, opposition or paradox. Writing gives an explicit verbal account of the implicit knowledge and understanding embodied in artistic practices and products while at the same time art may escape or go beyond what can be expressed by words and resist (academic) conventions of accountability.” (Sarconference2016.net 3 February 2017)

1.5EN4

According to a scientific database, “while on stage, a character can in a theater monologue reveal their emotions, thoughts and motives through their speech, speech that the other characters of the play presumably do not hear” (Tieteen termipankki 3 February 2017). In this thesis, this dramatic convention is reversed so that the speaking character, DAR, is not expected to respond.