1.2 Fragment 2

- Fragment 2, adapted from Hayles passage 2

Before responding to fragment 2, I will clarify how I understand some concepts that arise in the previous section. In 1.1, I mention algorithmic translation in passing as if its meaning were self-evident and common knowledge (1.2EN0). This is not the case. The definition of an algorithm is anything but obvious, even though we live in an increasingly algorithmic world (1.2EN0.5). In this research, algorithms are understood as sets of instructions or measures precisely defined to complete a task. In this thesis, the terms algorithmic and machine translation are used interchangeably, although strictly speaking algorithmic translation is a broader term than machine translation. Translation can be algorithmic without being performed by a machine. In theory, a human could translate according to an algorithm, but owing to its high computational capacity a contemporary computer is much more efficient at it.

In fragment 1, the Digital Artistic Researcher (DAR)—as I will henceforth refer to the I performing the rewrite or adaptation of Hayles’s book, in order to distinguish between my digital (virtual) self and my physical (apparently analogue) self—for their part mentions artistic research without specifying how they define it (1.2EN0.7). In order to have a reference point for my understanding of artistic research, I quote here the current definition put forth by the Performing Arts Research Center at my home university Uniarts Helsinki. According to the university, artistic research is “academic, multidisciplinary and collective research realized in the medium of art” (Uniarts.fi 20 September 2016). With regards to the current project, it is important to note that this research is realized in the medium of writing, which is 1) performative (i.e. presentational, utilizing means adopted from performance) (1.2EN1); 2) digital (created in and/or through digital media); and 3) translational (created in and/or through translation).

The (Non-)Gesture of Contextualization

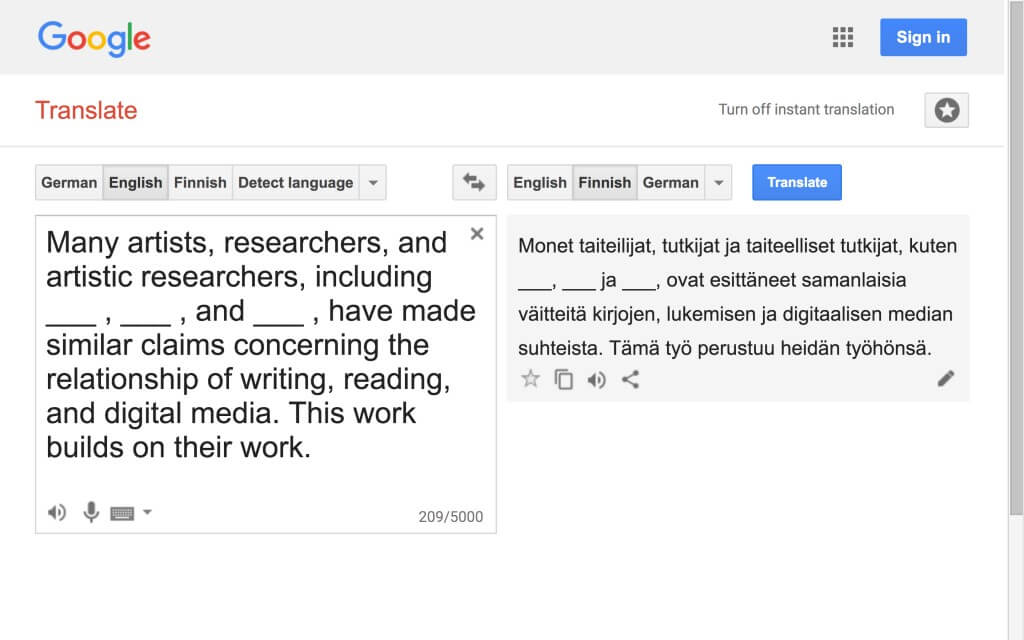

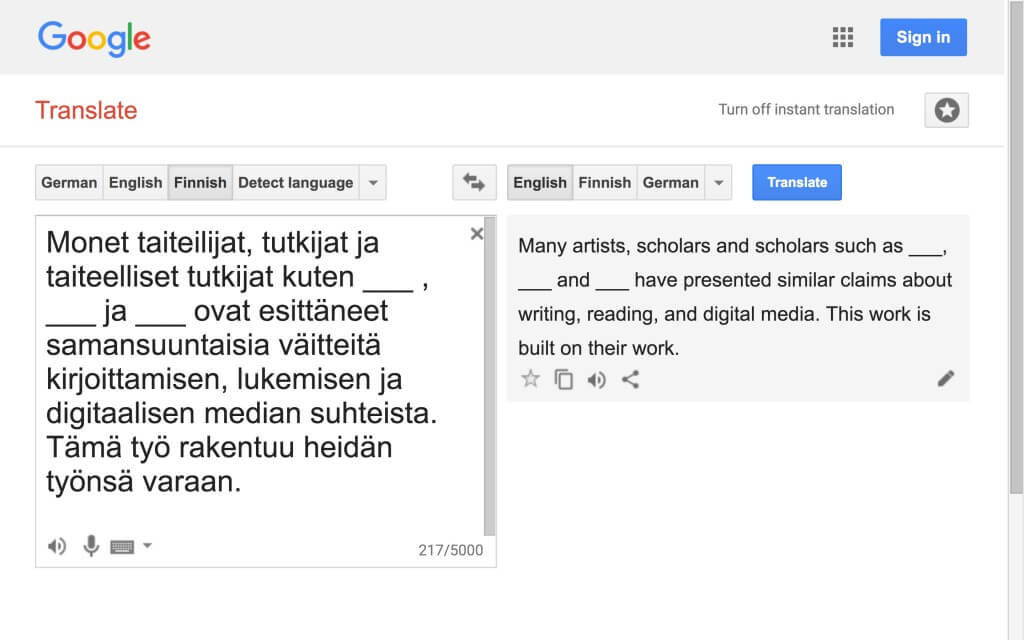

The gesture on display in fragment 2 begins in fact already in the last sentence of fragment 1: “This work is by no means the first to explore such a claim.” In the first sentence of fragment 2, DAR seemingly names the artists and researchers whose work precedes and is relevant to their work—seemingly because the places in the sentence where the names should appear are once again empty, as we see. In the latter sentence of the fragment, DAR acknowledges the dependence and indebtedness of their work to this other (albeit unnamed) work. In the context of fragment 2 and the model of research it proposes, this is—or would be—necessary to avoid the pretense that DAR is speaking of something that has never before been spoken of, as if they were creating a whole new tradition rather than joining an already existing one.

Here, I would briefly introduce the artists and researchers that DAR mentions in order to perform the gesture of contextualization—if it indeed is a gesture (1.2EN2). However, as the names are missing I must instead again reflect on the significance of the blanks left by DAR. As in fragment 1, what surely must be the most substantive information is missing from fragment 2: fragment 1 lacks the central argument of the research and fragment 2 the names of those who make up the tradition that the research attaches to. An unnamed tradition is not, at least in any ordinary sense, a tradition at all, just as a claim is not a claim until it is made. Thus, the absences are considerable.

Judging on the basis of two successive fragments with considerable gaps in them, DAR’s adaptation gives the impression of prioritizing structure, the design of a research model, over content. It seems that, on a structural level, DAR knows what they want but has not had ample time, could not bother, or has been unable to combine the structure with actual research content. Also, it is as if the missing names were mere placeholders that a structure of this kind requires but that are replaceable according to need and situation. As if DAR’s adaptation of Hayles’s book were an exercise in filling in the blanks, in which filling them in differently could potentially lead to countless different outcomes.

What does this say about DAR’s work and its nature? Is it simply unfinished? Or is it in perpetual motion and therefore resistant to attaching to any fixed tradition? Or is DAR simply a lazy researcher?

However, if we despite these questions at least for now side with DAR, we can also make the following hypothesis: the gesture of contextualization that DAR makes is not sincere and certainly not spontaneous, but rather the result of feeling obliged. In fact, it may well be that DAR prefers to think that their work forms a context of its own, no matter how ad hoc this context may be. DAR may not want to reinvent the wheel, but they do wish to justify their work through premises discovered during the research process rather than comparing their project to seemingly comparable projects, as Hayles does in her book (see adapted from Hayles passage 2). Also, it is worth noting that, in addition to mere structure and “blank blanks,” there are also “filled-in blanks”—that is information—in fragment 2: in a manner to be defined more precisely, this research deals with the relationship of writing, reading, and digital media.

Hayles, DAR, and I

Video 1.2.1 EN Sources referenced in video 1.2.1 EN: Hayles 2012, Raley 2018. NB: The reference Raley 2017 in the video is incorrect. The correct reference is Raley 2018.

Notes

1.2EN0

I borrow the term algorithmic translation from Rita Raley, who in “Algorithmic Translations” writes of the work of visual artist-poets Baden Pailthorpe and Eric Zboya, among other projects that utilize machine translation and mediation (Raley 2016).

1.2EN0.5

For a sociological perspective on algorithms, see Gillespie 2014EN. For a philosophical perspective on the relationship of algorithms and human cognition, see Parisi 2015. For algorithms as “black boxes,” see Pasquale 2015. For the relationship of algorithms and knowledge, see Rouvroy 2013EN. For the relationship of algorithms and moral accountability, see Schuppli 2014. For the relationship of algorithms and the physical environment, see Slavin 2011EN.

1.2EN0.7

I would like to thank my external examiner Mika Elo for drawing my attention to the fact that the name DAR associates with dar-stellen and dar-bieten, the German verbs for presenting and demonstrating.

1.2EN1

In “Performing Writing,” Della Pollock describes performative writing as a technology or technique that “collapses distinctions by which creative and critical writing are typically isolated” (Pollock 1998EN, 80).

1.2EN2

According to Marcus Terentius Varro, the Roman writer cited by Giorgio Agamben in Infancy and History, both poets and actors are indelibly involved with making gestures, as “the play is made by the poet, but not acted by him; it is acted by the actor, but not made by him.” In contrast to this borderline state of making but not enacting or enacting but not making, the emperor “neither makes nor acts, but takes charge, in other words carries the burden of [responsibility].” (Varro according to Agamben 2006EN, 140). For Agamben, Varro’s observation suggests what a gesture is (Agamben 2006EN, 139). In this light, certain claims could be made of this research: whereas DAR makes gestures, the ultimate responsibility for the research lies with me. On this stage, words are like actors in that they take different shapes and forms, transform.