The process which led me to this research started with a feeling. It was a feeling of “there is something special going on here”. I had this feeling as I participated in a dance improvisation class led by Adam Benjamin and CandoCo dance company in Brigthon in 1995. This was my first experience of a dance improvisation setting with dancers with and without disabilities.

As all feelings are, this one that I received during that workshop was a most embodied one. It was a sense of astonishment and wonder. This feeling buzzed around in my body – in my muscles and in my mind. For years, this feeling was like a background buzz that kept annoying me and trigging me at the same time. Today, this background buzz has disappeared as I have managed to articulate the wonder I had and the knowledge generated in this research process. It was this sense of astonishment and wonder that led me to this research.

In this lectio I wish to focus on the research process and the different turning points I experienced. It is the character of the research process itself that has made me develop the kind of practical-reflective artistic and art pedagogical competence that I have today and which I present in my thesis.

In order to go on, I need to do a short framing of the study. The research process has consisted of building up the Dance Laboratory, which is an artistic and art educational project in Trondheim in Norway. While building the project and developing the methodology I have investigated the meaning-making processes by the different participating dancers. What do they experience, what do they learn and how do they change, if they change? The group started with only 2 participants but then grew to 8 dancers during the year 2003–2004 when I collected the main empirical material for this study, consisting of interviews, video material and the researcher’s field notes. The Dance Laboratory still exists and the group consists of differently bodied dancers, with and without disabilities, both professionals and amateurs.

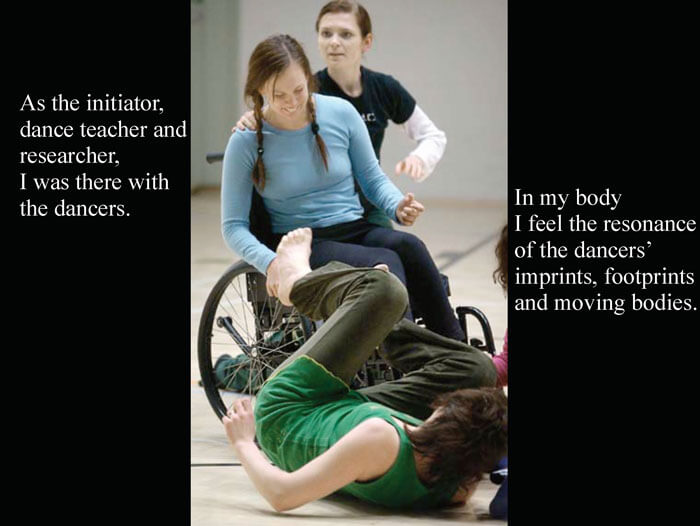

As the initiator, dance teacher and researcher in the group I was there with the dancers. In my body I feel the resonance of the dancers’ imprints, footprints and moving bodies. I can hear the sounds of their bodies when they spiral and twirl around each other; their feet and wheels when they run and roll across the floor; when they laugh and shout; when there is complete silence and focus on one dancing couple in the studio; when their bodies relax and they give each other a soft massage of the skull; the excitement when the wheelchair falls over with a dancer in it, and the feeling when my skin softened and opened up to give and take impulses from everybody in the dance space. As a researcher I was not an outside person, but I took part from the inside. I actively used my own body to understand and generate knowledge. In my case, the role of the dance teacher, choreographer and researcher are deeply connected. It was the mode of wondering and questioning I had while teaching and choreographing that turned me into a researcher. At this point, I want to show a short clip of the dance classes and interviews that are part of the empirical material for this study.

This was some footage from the site for my field work. This research can be positioned within a comprehensive hermeneutic-phenomenological research tradition. I have used myself not only as a research instrument, but rather as a research body.

This statement brings me to a French male philosopher of the last century, and to a Finnish contemporary female dancer and dance researcher. Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological project has intrigued me for years, and it still does. This research in a comprehensive way relies on his view on body phenomenology.

In her PhD thesis, the Finnish contemporary dancer and dance researcher Leena Rouhiainen has brought Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology into dialogue with Finnish freelance dance artists. Reading her PhD thesis served as one important turning point for my own research process. In a similar way that she describes how her research project was a result of a state of astonishment and also dissatisfaction with her understanding of her own field, my research is a result of a need to re-think questions about what dance is, who dance is for, which dancing bodies that have admittance to the stage, what dance can mean in different people’s life and how dance can be taught and choreographed.

One aspect of Merleau-Ponty’s mode of philosophizing that has been important in this process is his urge to see beyond ordinary and established knowledge and categories: to re-view facts, conceptions and conditions that are taken for granted. In Merleau-Ponty’s case, the conditions taken for granted were previous philosophical and scientific positions. In my case, the conditions taken for granted have to do with the aesthetics of dance, how dance should be taught and who that has the possibility of being defined as a dancer.

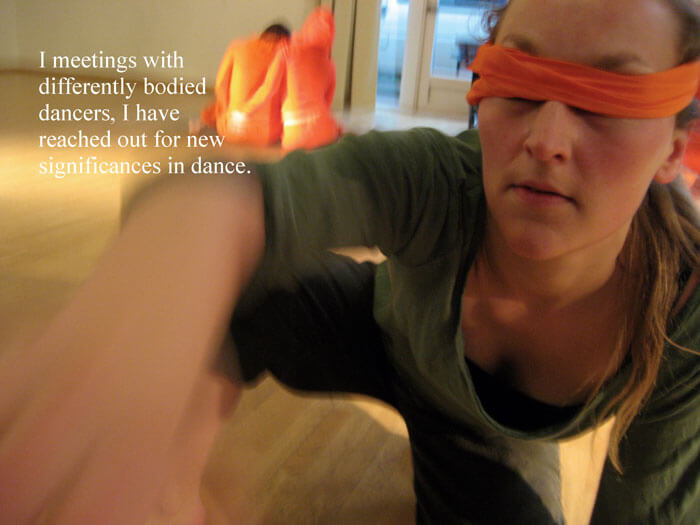

My whole research process serves as an example of what Rouhiainen investigates in her PhD work: the lifeworlds of (Finnish) contemporary freelance dance artists. As a dance artist and researcher I confirm what she concludes: that the life of a freelance dance artist basically is concerned with a questioning and transformative mode of existence. Through the way I work, and with this research, I scrutinize the heritage of contemporary dance that I am a part of. My meetings with differently bodied dancers in improvisation have given me the opportunity to question existing conditions and categories in the dance heritage I am part of. I investigate and debate the role of the dance teacher, the dancing body and my local field of dance. In that way, my wish to enter this research process is grounded in the fact that it had resonance in my lived body and life as a dance artist and teacher. Having read Rouhiainen’s work, I could now live and act my own research process, instead of only “thinking it”. In this, and through this process, I have reached out for new significances in dance.

Today I explain that feeling I had on that first workshop in Brighton, with the fact that the way dance was taught and used there was a way that opened up many spaces in dance. As a participant I entered all those spaces but I did not have the understanding or vocabulary to articulate any thing else than this feeling of “something special going on”. Through this research process at hand I have created that understanding and vocabulary.

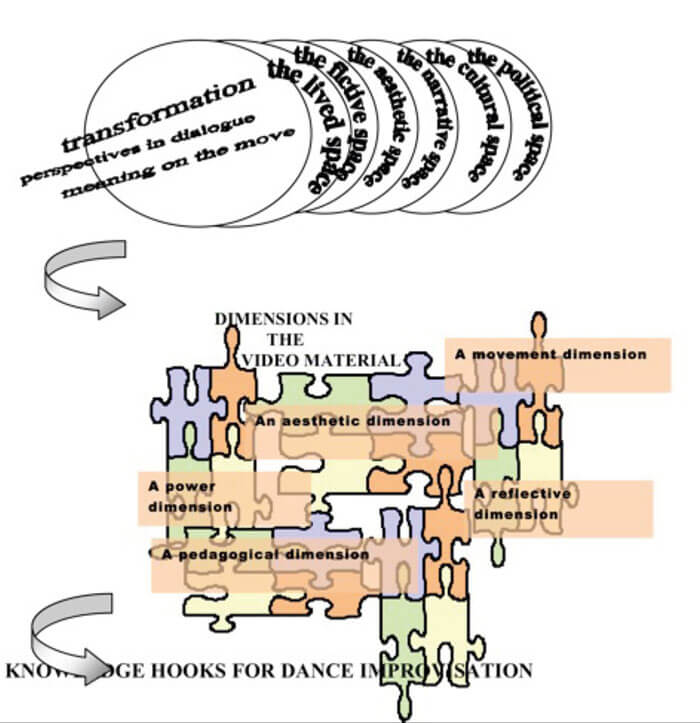

The concept space can be seen as one of the theoretically loaded concepts that play an important part in this research process. The creation of different perspectives on space as a tool to look at the research material with was another central turning point in the process. This was a turning point which opened up the whole empirical material. Through the lenses of different perspectives on space in dance that I defined, I could now describe, organize and interpret the empirical material collected in the Dance Laboratory, as shown in figure1.

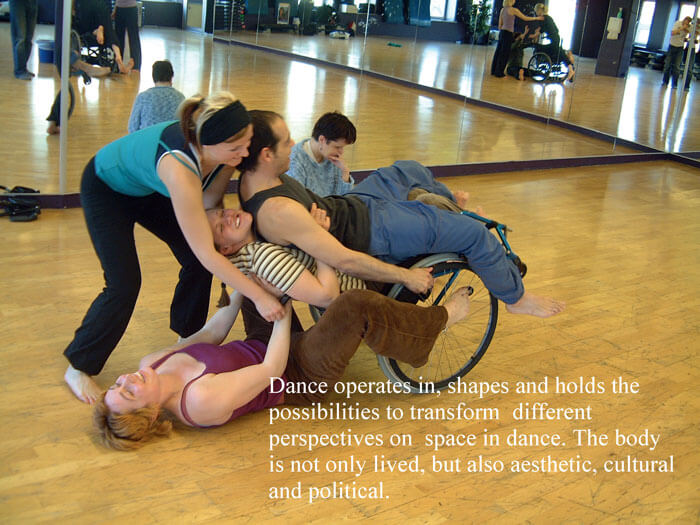

I created perspectives on space in dance which I call the lived, fictive, aesthetic, narrative, cultural and political space. From my perspective as a dance teacher and researcher in the Dance Laboratory, dance operates in, shapes and holds the possibilities to transform these spaces. Each and every one of these spaces holds a lot of sub-spaces; in other words, each space is endlessly spacious, ready for negotiations. Therefore, the teaching of dance holds the possibility to be both spacious and generous, investigating and redefining these different spaces.

I use the concept space based on my assumption that space, dance and body cannot be separated. Valerie Briginshaw argues that space, like subjectivity, is a human and social construct. Space has a history which is tightly connected to a history (histories) of the body, because it is by means of the body that space is perceived, lived and produced in the first place. The rational subject inherited from Descartes, is reduced to co-ordinates in time and space, and this time and space are seen as mathematically measurable which has given birth to the idea about the body as a spatiality of position. According to Briginshaw, this means bracketing off other ways of experiencing time and space. Leaning on Merleau-Ponty, Gallaugher and Zahavi instead put forward the body as a spatiality of situation. This is a frame of reference that applies to the lived body as perceiver and actor.

The wish to create my teacher and researcher perspectives on space in dance is because I acknowledge the body as a spatiality of situation. When I observe and take part in the Dance Laboratory, roll around over and under the dancers, run across the floor, hear the studio filled with laughter, blush because I am moved, sense the tension between dancers struggling to find out, fly on top of tilted wheelchairs, listen to quite different dancers’ reflections and sweat as I try to create choreographic material, this is by no means a neutral, objective or one-dimensional space. This space is very lived, so emotional, it is aesthetic and there are ideological, philosophical and political parameters hanging in the air, in space, in the bodies, in the dance. In each and every aspect this is a space with huge aesthetic and pedagogical implications and possibilities. It is a space for learning – again, at its best, a generous and spacious one.

My choice to define different perspectives on space in dance as lenses to look at the empirical material with is an attempt to go into dialogue with some of Birginshaw’s most interesting questions: What and how space means in dance, how it is possible to think of space differently, and what this means for dance and subjectivity. I agree with Birginshaw, that through a focus on space in dance, dance can challenge, trouble and question fixed perceptions of subjectivity and fixed cultural narratives about different bodies.

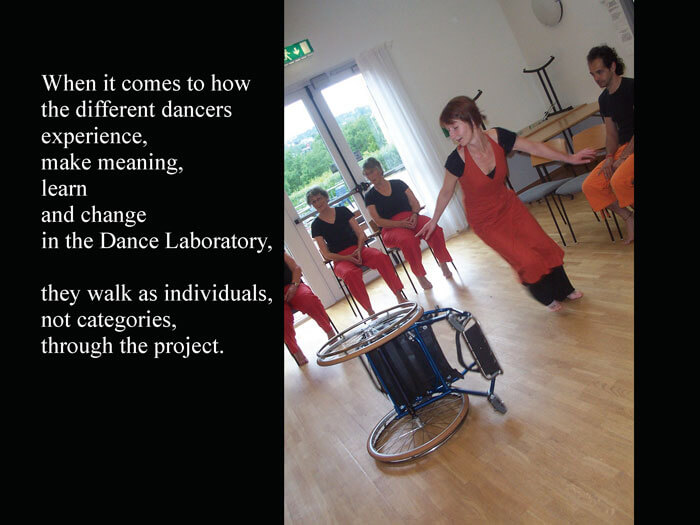

Another important turning point in the research process was when I finally understood the uselessness of traditional categories to organize the research material. I really had to make an effort in order to understand that I could not use different traditional categories like “disabled” and “non-disabled” to organize the empirical material, as this lead to simplification. Instead, I had to stretch out and see beyond my existing horizon of understanding. When it comes to how the different dancers experience, make meaning, learn and change in the Dance Laboratory, they walk as individuals, not categories through the project.

Put very simply: just because you are disabled, you do not necessarily experience and learn the same things as another disabled dancer. And also, of course, “disabled dancers” are a very heterogenous group. Being a blind dancer, for example, is very different from being a dancer with cerebral palsy. This way of avoiding traditional categories as a starting point has been a complex way to go for me as a researcher, as it has challenged me more deeply than I could expect. In retrospect, it is easy to say that obviously, there is no other way to go. When I was in the process, it was not that easy, and I had to make an effort to do it. In a way, I suggest I was in the process of resisting dominating cultural narratives, including a Western urge to categorise. To follow the dancers as individuals instead of categories instead made it possible for me to see the dancers as individuals-creating-community instead of splintered categories existing side by side in a group.

I have learnt that it is never enough to categorise people and know already who they are, how they will move or what they will learn. On the contrary, the often tacit feeling of “I know already what a boy in wheelchair is like” should function as a warning sign. This feeling of “knowing already” is rooted in conventional and cultural assumptions about people using wheelchairs. People are bodies, yes, but they are not a body-category that holds certain fixed characteristics of how they experience, learn, create, think, relate, dream and contribute. It seems very easy to create categories based on the body, but this means pushing people together in simplistic and fixed ways. History tells me that this is both devastating and dangerous.

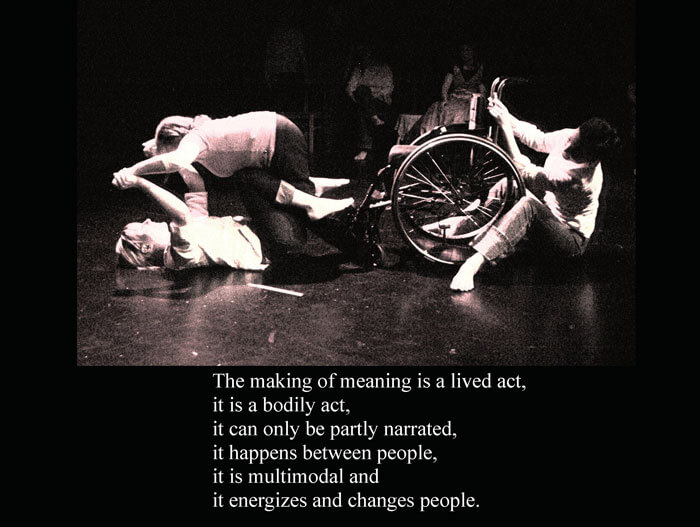

When I started this research project, I was surprisingly little aware of the aesthetic, pedagogical and political potential in the material. I was somehow very focused on the dancers’ inner worlds, what they experienced inside of them. Through the research process, and with the steady guidance of my excellent tutors Soili Hämäläinen and Ann Cooper Albright, my view on meaning-making as such has changed hugely. For one thing, I have understood that meaning-making is not just an “inner”, personal thing and “meaning-making” is also not only a “thought” thing. Instead, the making of meaning is a lived act, it is a bodily act, it can only be partly narrated, it happens between people, it is multimodal and it energizes and changes people.

One of the questions I asked myself as an impulse to this research project was who dance is for. As a result of the project, my clear and loud response to this question is that dance is for every body. I strongly suggest that dance in contemporary time becomes more relevant when the field manages to embrace more and differently bodied dancers into the dance field. I suggest that the dance field needs a de-construction of the conventional cultural narratives, which right from the start tell about the dancer as able-bodied. I also suggest that this is one main responsibility for contemporary dance artists, choreographers and teachers: to make dance as an art relevant to the world as the world is today through embracing differently bodied dancers.

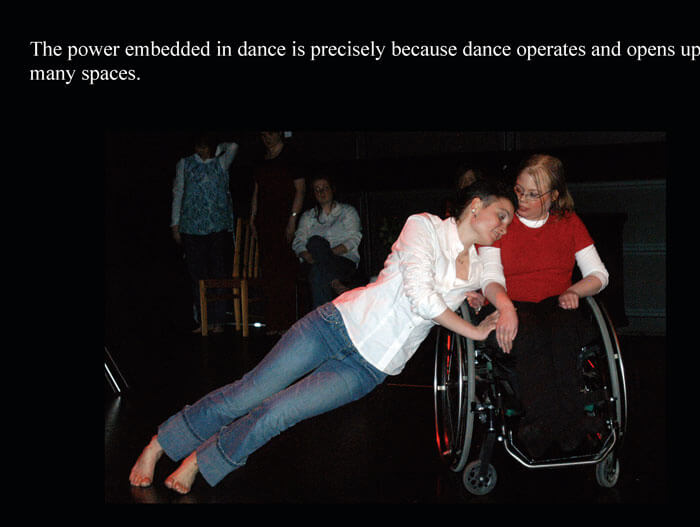

The dance field fails to communicate its importance if it creates a distance from groups of bodies, thus tacitly saying that dance is only for special bodies. I want to resist this way of positioning dance at a distance from many bodies. This is – dare I say it – a wrong way of using space. Space should be used to make different body-subjects reach out and find out what dance can be in their bodies. Dance offers important meaning-making possibilities for different body-subjects. The awareness of the dance teacher – and the choreographer – is the key to releasing the power that is embedded in dance. This power embedded in dance is explosive precisely because dance operates in many spaces. Dance as an art form offers information about these different spaces.

As a result of this research process I have developed a practical artistic and dance pedagogical competence where I try to stay present in all these different spaces I experience in dance class. As I start to round off this lectio, in the following I will try to describe what this knowledge and competence consists of.

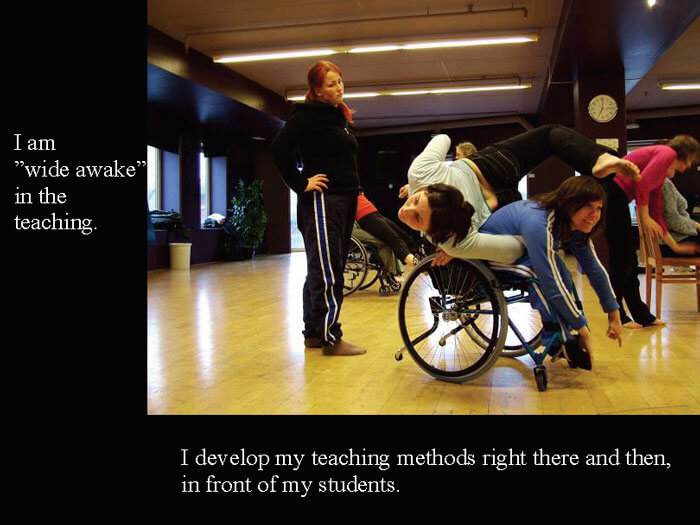

I enter the dance class with a heightened phenomenological awareness and I am “wide awake” in the teaching. As I teach, I use my sensations and feelings as feedback. This sensuous feedback that I open up for through a listening into the moving and ever-changing space guides me when I make teaching decisions in class. As I listen into my sensations and make decisions I am highly attuned on my “inner dialogue” that goes on inside of me as I teach. I dwell in a constant flow between my sensuous experience and reflected thought while teaching, in this focus being inspired by Eeva Anttila and her research on the affiliation between the conscious body and reflective mind.

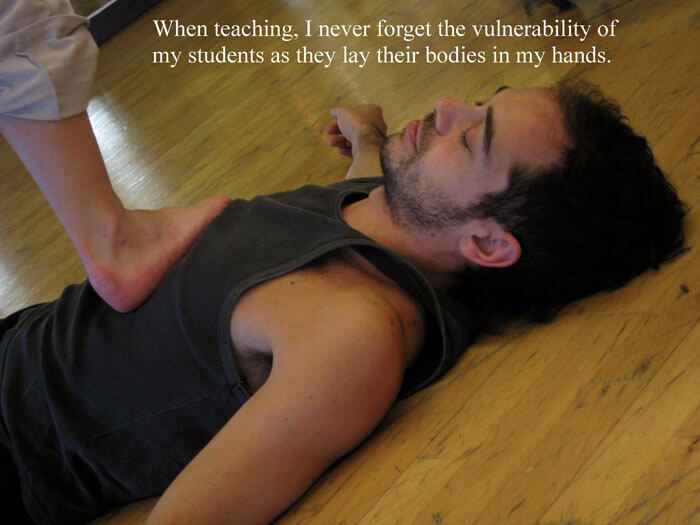

Through my research process this “inner dialogue” is not only an annoying buzz any more, but instead an informed dialogue influenced by existing theory and the research committed by others. This makes me capable of handling the different situations I dance into as an improvisation teacher. I am prepared when I trip over the splinters of a dualistic worldview in dance class. I work on avoiding the split that seems to exist between the categories of different bodies that we have created in dance and society and I am aware of the power issues that arise in a dance class with differently bodied dancers. While teaching, I also acknowledge my own vulnerability as a constantly problem-solving dance improvisation teacher. I need to develop my teaching methods right there and then, in front of my students. At the same time, I am aware of my own power and dominance in class, and I never forget the vulnerability of my students as they lay their dancing bodies in my hands.

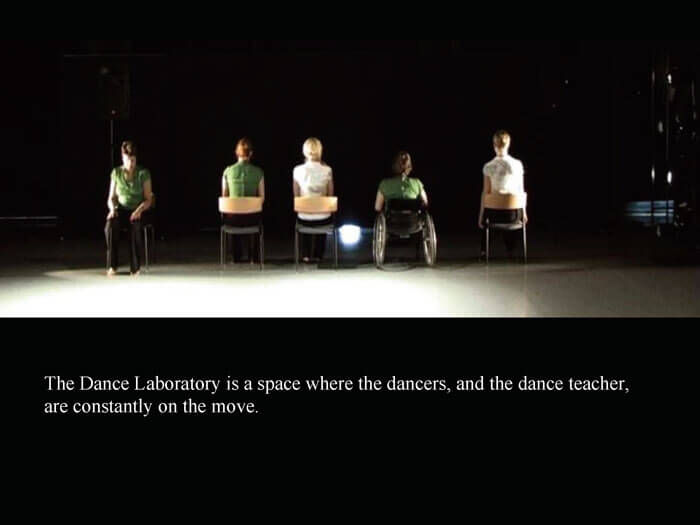

Thus, applying an abductive research logic, the way I own the knowledge presented in this thesis has a reflexive, practical-pedagogical character. While teaching, and researching my own teaching, I constantly switch perspective from doing to zooming out and observing and dialoguing with relevant theory. For example, my theoretical knowledge about the consequences of a dualistic worldview is at work in the way I manage to handle practical-pedagogical situations where a tricky situation suddenly opens up a political space in the dance class. In a similar way my knowledge about phenomenology, is not foremost of a strictly theoretical character but again, rather of a practical-reflective one. When I teach, I enter a state which, again, can be described as a heightened phenomenological awareness. I am not only experiencing, but I am reflectively attuned on my experience and how I can use that experience while teaching. The teaching situation is an aesthetic experience, I live the teaching situation deeply; it energizes me, influences me and changes me. The dance improvisation class is a space where I learn as dance teacher. As the results presented in this thesis tell about, so do the dancers. The Dance Laboratory is a space where the dancers, and the dance teacher, are constantly on the move.

With this I am closing this lectio.

26.10.2009

CC BY NC ND